Dearest,

1.

I once overheard a writer say that the blank page is a dare wrapped in possibility—and feels very much like an invitation to do something brave or, more likely, ridiculous. You sit down, the world outside your window, and there it is: silence.

Some days, the blank page feels like an old friend who loves you no matter what—you can show up with greasy hair and half a thought, and it’ll wait patiently. Other days, it’s a hostile situation. I know you know.

I think of Emily Dickinson when I’m stuck like this: “If your Nerve, deny you—go above your Nerve.” And I think, Well, that’s just great, Emily. I can barely go above my laundry pile, let alone my nerve. But there might be some truth in there. Perhaps you stare down the page and start anyway, even though you’re convinced that what comes out will be crap.

And it will, at some point—there’s no way to avoid that. No shortcut, no secret handshake. Some call it writing by the seat of your pants, and for poetry especially, it feels almost mandatory—to write and lean into the uncertainty. It’s terrifying, this uncertainty of what will spill out onto the page—but this is what writing demands.

Anne Lamott refers to it as the “shitty first draft” and Ernest Hemingway said, “The first draft of anything is shit”—so yes, it’s messy. It’s sprawling. It’s the literary equivalent of spilling your purse in public. But it’s honest, and honesty is the thread that pulls the whole tangled what-the-fuck-is-this together.

2.

Truth be told, I’ve been staring at blank pages awhile. I thought the start of the year will be generative for me, but so far all I’ve had these past two weeks are the unfortunate discovery that I don’t like cinnamon in my coffee, my fittonia has started to wilt, and panic attacks that bring me to my knees. And do you know how hard it is to get up with almost-forty-year-old knees?

There have been days when my writing practice feels like swimming against the current—always harder than I’d hoped, with words resisting my grasp. But I wrestle with it anyway. Wasn’t it the inimitable Nora Ephron who once said that the hardest thing about writing is writing? So much yes to that. But I’m also a firm believer that writing requires that we show up regularly, constantly, consistently. And each time I return to the page, I am reminded that this whole shebang is less about the product and more about the practice.

All I have to do is embrace the terror that comes with starting something new. Easy, right? Ha. Then I can let the words tumble out in whatever form they needed to take, unbothered about cohesion or clarity. Could be chaos on the page. Lines crossed over each other, paragraphs stretched out like an endless road.

It’s easy to fall into a trap thinking of writing as an obligation, something that must be done. But Jami Attenberg reframed this for me:

“I’ve learned to transform the nerves into enthusiasm for the most part. My approach is: “I get to write a novel” versus “I have to write a novel.” And I think about what I desire. What kind of stories I want to tell, what voices I want to give life to in the world.

…The words do so many different things for people. If your writing is for comfort, let it comfort you. If your writing is for process, let it be for process. If your writing is to change your life or even the world, let that change roll. If your words are a war cry, for the love of God, please howl.”

She said, “I get to write,” not I have to. That’s a good reminder when I’m slogging through the muck. I get to write. Even when it’s hard. The opportunity to sit with your thoughts and be vulnerable and create something, even if it’s only for yourself—isn’t that worth showing up for? I get to write poems! Imagine! In this economy!

3.

But you know—sometimes things actually go well. Devin Kelly talks about this—the narrative of the surprising and wonderful first draft:

“I want to say that there are different kinds of work, and that both discipline and work can look like many different things. Sitting down to write at 6 in the morning every day can be a kind of discipline. Writing a stream of conscious narrative can come from a place of discipline. The ability to structure and offer discipline to your life can come from privilege, whether that’s the privilege of money, or time, or job security. Some people create discipline out of lives that are filled with work.

This idea—that discipline isn’t a one-size-fits-all uniform but rather a patchwork, stitched together by our circumstances—is one I keep coming back to. For some, discipline looks like a tidy, colour-coded schedule. For others, it’s scribbling a few words on a receipt during a five-minute break. Both are valid. Both are enough.

I think about how life shapes the ways we write. Maybe you don’t have the luxury of sitting down at 6 AM every day. Maybe your writing happens in the margins of an overfull life, between shifts at work or while a baby naps. That’s discipline—you are actually carving space where there is none, and honouring your writing even when it feels impossible.

And yes, the notion of a first draft that’s good feels like a kindness. But even these moments of creative clarity don’t emerge from nowhere. They’re often the product of doing the work.

I’ve had poems that have poured out of me as if they already existed long before me, and I was just the vessel. When these drafts happen, it feels magical, even a little bewildering. I always begin each poem without any expectation of where I’ll end up—but there are some that emerge fully formed, and I have no idea how or why that happened.

I think of them as gifts handed to me by the universe. It sounds a bit woo-woo—but all I had to do was listen, and they’ve written themselves very quickly and that was it, they felt finished. And then there are poems that take me years to write and revise.

In the same essay, Kelly continues:

“Natasha Oladokun, one of my favorite contemporary poets, mentioned how Li-Young Lee sometimes asks himself, “What impulse was I privileging in draft #2 that’s been killed by draft #17?” What a generous and self-interrogating thought, to understand that the work of working on something doesn’t always make that something better.”

“…I guess what I am trying to say is not that our first drafts are always absurdly beautiful, or that we should all stop revising, but rather that there is a language of surprise and generosity that exists within the confines of the first draft that can, at times, be beneficial to us as writers and people. And I think that what you want from your own writing depends on what you want from the world of writing.”

When I’m deep in the throes of revision, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that more work will always make the poem better—that another line break, another reshuffling of words, will finally unlock its potential. But it isn’t always true. Sometimes, the hardest and most important work of writing is knowing when to step back, to resist the urge to keep, er, tampering~, and to let the poem simply be. There’s a fine line between refining something and trying to force it into a shape it was never meant to take.

And then there are poems that don’t need seventeen drafts to find their form—they just need a little air, a little room to stretch out and exist as they are, flawed and alive. Others, though, demand patience. They linger for years, resisting closure, waiting for something in me to shift.

I’ve learned that these poems don’t just need more time on the page—they need more time in me. They need me to live a little longer, to become the person who can finally make sense of what I was reaching for back then. It’s a strange kind of collaboration, this act of waiting for a poem to meet me where I am, and for me to meet it where it’s been all along.

It’s humbling, too, to realise that some poems know themselves better than I do. They remind me that writing isn’t about control; it’s about trusting the poem to find its way and trusting myself to listen when it finally speaks.

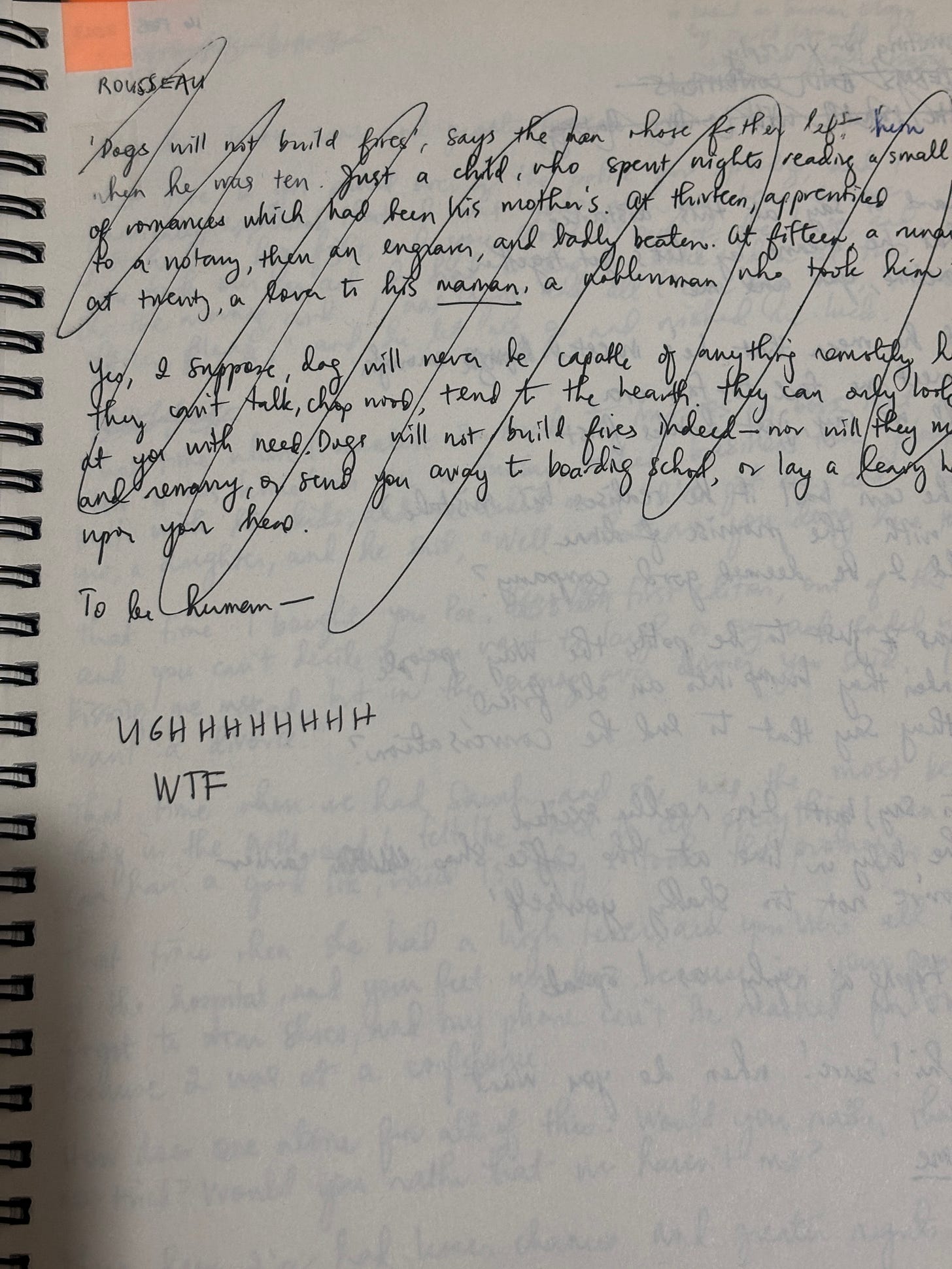

Here is something I wrote in 2011 in its very first iteration:

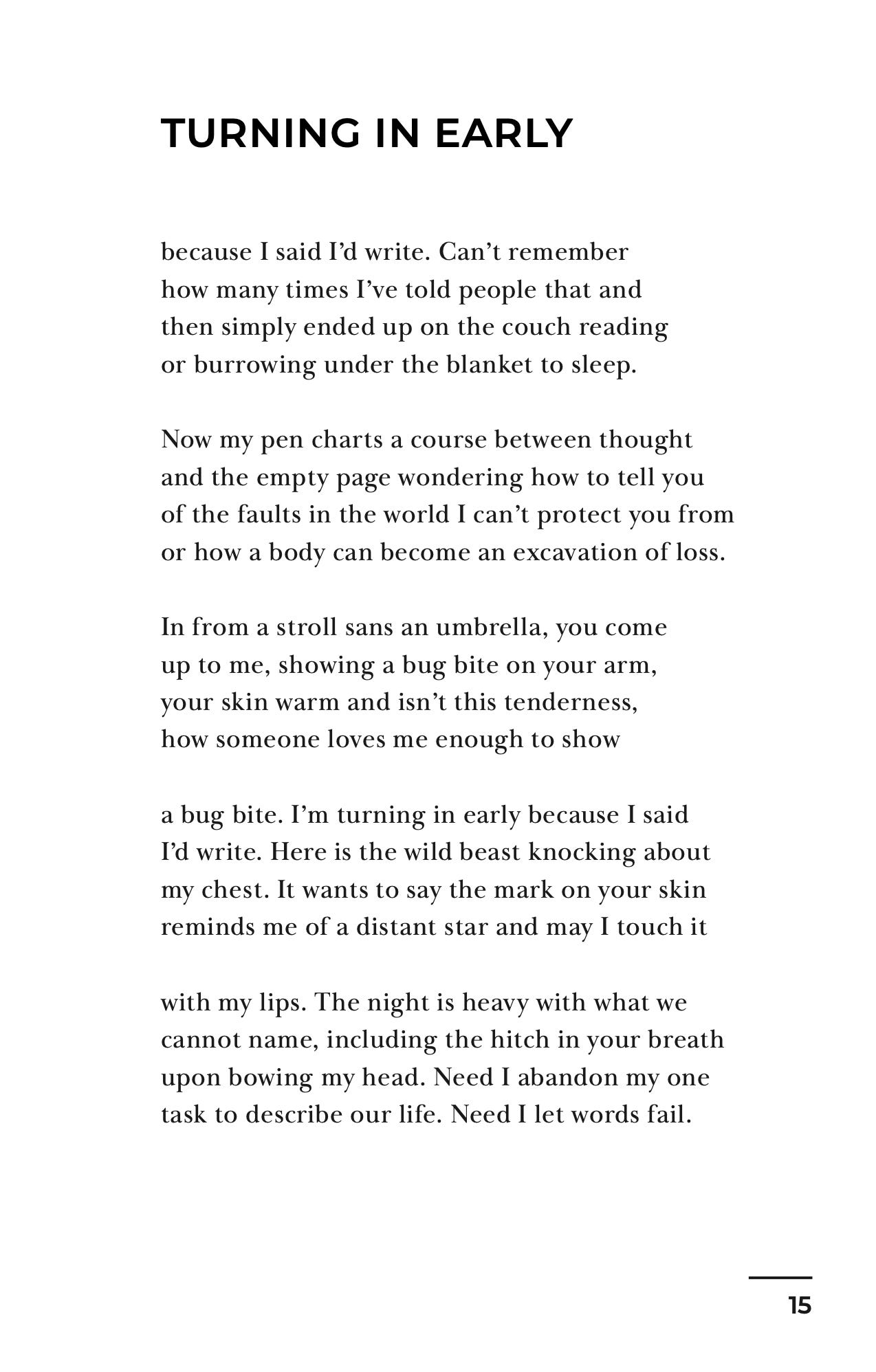

And here it is, thirteen years later in my chapbook:

4.

Of course, there’s no one proper way to write. Some poets embrace spontaneity, and fling themselves at the page a la Allen Ginsberg, who described writing the first draft of “Howl” as such: “I had nothing to gain, only the pleasure of enjoying on paper those sympathies most intimate to myself .”

Others tinker and nudge and polish until the words behave. I do both, depending on the day and the snacks available. Some drafts are furious floods, others slow, stubborn drips. Both are valid. Both are necessary.

How does one do this in poetry? I know the apprehension that can come with it. Sometimes, too, feelings of being inadequate. But here’s the thing—you can do it. The point isn’t to arrive in an utterly impressive fashion—it’s to keep going.

I write my first draft—roughly, meanderingly—in this manner:

Step 1: Start with an idea

It could be a memory, a question, a conversation, or something you noticed during your commute. Whatever it is, grab it. Don’t worry if it’s not “good enough.” Ideas don’t have to be good—they just have to exist.

In a previous In Surreal Life visiting artist call, Kaveh Akbar, ever so brilliant, said that writing is maddeningly linear—you really have to do the work.

Once you have your idea, give it a little love. Daydream about it. Jot down some thoughts. Let it hang out in your brain for awhile. (And in case you’re interested—here are some poets answering, “How do you know when it’s time to start drafting?” among other questions on first drafts.)

Step 2: Do some research

Depending on what you’re writing, research might mean digging through books, interviewing someone, or Googling until the end of time. Gathering inspiration—reading, people-watching, or listening to that one song on repeat—counts as part of the whole affair.

It was also Kaveh who emphasised the importance of organising your material and research when you’re writing. That one must try to be voracious in what we consume—to be rigorous and unprecious. Everything you read, everything you hear, everything you experience—you must take your materials seriously because they have history and integrity. Don’t rush them to the finish line. Let them take their time to become whatever they’re meant to be.

Step 3: Organise your thoughts (kind of)

Some people love outlines. Some love a freer approach. Try a list of points you want to hit or a scribbly diagram that only you understand. Or skip the formal structure entirely and believe that things will fall into place later. Writing is, after all, an act of faith.

Step 4: Write the darn draft

This is the part where most people freeze. The blank page stares back at you like a judgmental cat. Ignore it. Take a deep breath, and write anything.

The first draft isn’t about getting it right—it’s about getting it down. Write fast. Write messy. Don’t stop to fix typos or rethink that clunky sentence. Just keep going. Momentum is your friend here.

If you get stuck, skip ahead to the part that feels easiest. Write the middle before the beginning, or the ending before the middle. Nobody will know. You’re the only one in the room, it’s okay, give yourself permission.

Step 5: Take a break

When you’ve wrung every last word out of your brain, step away. Walk the dog. Watch bad TV. Do anything that isn’t writing. Let your draft marinate for a day or two—or longer, if you can stand it.

This break isn’t procrastination—it’s part of the process. Distance will help you see your work with fresh eyes, which is crucial for the next step.

Step 6: Revise, revise, revise

Now comes the fun (and by fun, I mean gruelling) part: revision. Revisit your draft like a sculptor with a chisel—or, if you’re feeling dramatic, a demolition crew.

First, look at the big picture. Does it make sense? Are the ideas connected? Is the form doing what it’s supposed to do? If you can, fix the structural stuff first. Then, zoom in on the details—clean up the language, trim the fluff, and make it sing.

Is this the end-all and be-all of revision? Heck no. But it’s a start. I would probably write more about revisions in the future—but I want to hold space for it here and acknowledge that it is very much part of the whole gig.

5.

Walt Whitman wrote:

“The secret of it all, is to write in the gush, the throb, the flood, of the moment – to put things down without deliberation – without worrying about their style – without waiting for a fit time or place. I always worked that way. I took the first scrap of paper, the first doorstep, the first desk, and wrote – wrote, wrote. By writing at the instant the very heartbeat of life is caught.”

Perhaps, in their own way, every draft is inherently flawed—but what the first draft does is free me from the pressure of the ideal. In the end, to write is to confront our own fear—and to accept that the first draft is a refusal of the “perfect” moment or the “right” words.

The first draft isn’t a finished thing—it’s a living, breathing conversation between you and the page. It invites you to respond, to shape and reshape, to stumble your way toward meaning. And in that act of engagement is the reaching for connection. After all—as Elizabeth Alexander says in a poem: are we not of interest to each other?

Here’s a writing prompt:

Begin your piece with the line “What I don’t know yet…” and let it guide you into an exploration of curiosity, uncertainty, or discovery. Use this as an entry point to dive into what’s unresolved in your life—questions about love, identity, memory, or the future. Let your writing unfold as a conversation with the unknown, weaving together what you do know with the possibilities and fears of what you don’t.

For added depth:

Imagine the line as the beginning of a letter to someone or something that holds answers—your future self, a loved one, or even the universe.

Incorporate sensory details that reflect the tension or wonder—textures, colours, sounds, or tastes.

Let your writing evolve into a meditation, embracing the beauty of not knowing and the paths it opens.

What landmarks or trails are beginning to emerge? What does this reveal about where you want to go? How does focusing on what you don’t know help you see the possibilities waiting to be explored?

Finally, a poem:

Twenty-One Love Poems [Poem II]

Adrienne RichI wake up in your bed. I know I have been dreaming.

Much earlier, the alarm broke us from each other,

you’ve been at your desk for hours. I know what I dreamed:

our friend the poet comes into my room

where I’ve been writing for days,

drafts, carbons, poems are scattered everywhere,

and I want to show her one poem

which is the poem of my life. But I hesitate,

and wake. You’ve kissed my hair

to wake me. I dreamed you were a poem,

I say, a poem I wanted to show someone…

and I laugh and fall dreaming again

of the desire to show you to everyone I love,

to move openly together

in the pull of gravity, which is not simple,

which carries the feathered grass a long way down the

upbreathing air.

Yours,

T.

I feel I want to learn this whole piece by heart, every single word of it, until the day, when my novel is done and I am asked ‘how did you do it?’, I can quote it like Jeff Goldblum quoting George Bernard Shaw on the Steve Colbert show. But for now: thank you so much for this wonderful and unexpected gift on the final stretch of my novel journey.

This felt very inspiring and encouraging to read as I try to claw my poems out into existence. Thank you kindly for writing it and putting it out here so I can read it.