Dearest,

1.

It takes four minutes and thirty-four seconds to listen to Þú ert jörðin by Ólafur Arnalds. About fifteen seconds to walk from my desk to the refrigerator, where I stood for a good ten minutes wondering if I should break the dark chocolate open. Some days it takes me almost all morning before I can get out of bed and decide to live. Some showers could take an hour or two. It took me one evening to learn how to cook the perfect smoky red lentil soup. It took me my whole life to get here, barefoot at past one in the morning, trying to write about time.

There is a memory I return to often: one afternoon when I found myself sitting by a window, watching the light shift across the room. In those days, I was restless, driven by an unspoken need to fill every moment with purpose, to ward off what seemed like emptiness. Waiting, in any form, felt like a transgression—we’re conditioned to believe that every second of our lives should be spent doing something: moving forward, making progress, crossing things off the list.

I did not yet understand the subtle work that takes place when I allow myself to pause. It was only through the slow accumulation of years that I began to see that these moments were not empty. In the space where time seems to stretch, where the noise of life fades, I find that ideas begin to stir. Of course, they don’t always announce themselves loudly—

2.

It’s remarkable how time, when given space, reveals its true nature—not as a void to be filled, but as a vessel holding the potential for growth and transformation. I’m waiting for myself to arrive, to become fully present at the moment.

“To tell the truth again, I have not yet begun my literary work…some of the characters have grown old without managing to be written. In my head there is a whole army of people asking to be let out and waiting for the word of command. All that I have written so far is rubbish in comparison with what I should like to write and should write with rapture…

All that I now write displeases and bores me, but what sits in my head interests, excites and moves me—from which I conclude that everybody does the wrong thing and I alone know the secret of doing the right one. Most likely all writers think that. But the devil himself would break his neck in these problems.

Money will not help me to decide what I am to do and how I am to act. An extra thousand roubles will not settle matters, and a hundred thousand is a castle in the air. Besides, when I have money—it may be from lack of habit, I don’t know—I become extremely careless and idle; the sea seems only knee-deep to me then...I need time and solitude.”

— Anton Chekhov, written 27 October 1888 (from Letters of Anton Chekhov to His Family and Friends by Anton Chekhov, translated by Constance Garnett)

When I write, I try to enter a state of quiet receptivity, where the work of attention can unfold. I try not to force the words—I trust that they will lead me where I need to go. This creative mindfulness is a way of grounding myself in the present, without the pressure of immediate results.

But how often do we allow ourselves this kind of patience?

3.

I’ll admit it: revision is not my favourite part of writing. There are poems I’ve let lie for years because they didn’t feel ready. And that’s okay. Sometimes, the self that first wrote the poem isn’t the self that can revise it. We change, and so does our work.

Consider my poem, “Gargantuan,” which eventually found a home in Narrative earlier this year, and which is included in my chapbook, And Yet Held. It only took me thirteen years:

Revision is like pulling out the weeds, giving your poem space to breathe. It is the process by which we refine our work, as well as our understanding of ourselves. It is also a practice of trust—trusting that the work will reveal itself fully only when it is ready, and trusting ourselves to recognize that moment.

That being said—some revisions are more painful than expected, and frustrating as hell. The other day, I was revising a poem I thought was almost done. I thought it only needed a few tweaks here and there—but the more I revised, the worse it got. It didn’t matter if I took things out or put them back in—whatever I did, it only made it more deplorable. I sat there with disbelief all over my face: I have a fucking ugly baby. I was its mother, and it was a fucking ugly baby.

So yes—some works need to lie fallow. At least for now. I know I’m mixing my metaphors. I have no excuse.

What I am saying is: there are poems that don’t make themselves known to me until after a decade or so has passed. They needed time. They needed my life to happen before I can figure out what I was trying to say. So I tell myself: put the poem down. Walk away. Wait.

4.

Whenever someone asks me, “Is this about you?” or “Did this really happen?” when referring to my poems, I’m reminded of something F. Scott Fitzgerald is purported to have said: “All my characters are Scott Fitzgeralds.” I suppose I am inclined to say yes—my work, whether I intend it or not, is at some point a reflection of the self—however filtered or refracted that may be.

The brilliant poet Diane Seuss said in an interview, “I needed to build an urn that would exist beyond me.” Poetry is constructing something that holds not just our own experiences but the collective experiences of those around us. The poem holds fragments of our lives, our imaginings, our perceptions—and yes, our truths.

And so, when I say that my poems are about me, I mean that I am the teenage boy sweeping fallen leaves on the pavement, I am the artist drawing in her sketchbook while listening to a YouTuber comment on the downfall of Mr. Beast, I am the dog nestled in a handbag that someone is trying to sneak into my building. I am the moon shining over tents in Gaza, I am the man in a Duane Michals photograph watching flowers die, I am the flowers. In the act of writing, I become each of them, just as much as I remain myself.

But this, too, requires patience and care. Jincy Willett’s question lingers: “Whose lives can we plunder?”

It is something every writer must grapple with—when we write from life, we are borrowing from the experiences of others, as well as from our own. This borrowing is not without its ethical considerations.

Waiting then becomes a form of respect, a way to ensure that our words do not rush ahead of our understanding. Ultimately, we are asked to navigate the fine line between revelation and intrusion, between telling a story and honouring the lives that have shaped it.

5.

The writing life is full of unseen moments, times when nothing seems to be happening. These are the spaces where ideas quietly gestate, where the work matures beneath the surface. Waiting is a way of allowing our creative impulses to find their form in their own time.

And what would waiting be without its trusty sidekick, anxiety? That ever-present shadow, that intrusive thought: “Are you sure this is worth it?”

“When I say ‘I fear’ — don’t let it disturb you, dearest heart. We all fear when we are in waiting-rooms. Yet we must pass beyond them, and if the other can keep calm, it is all the help we can give each other.”

— Katherine Mansfield, written 14 October 1922 (from The Journal of Katherine Mansfield, 1927)

I think sometimes we are afraid, not because the waiting is empty, but because it is full—of possibilities, uncertainties, and the unknown that lie ahead.

Recently, I received a rejection from a literary magazine more than a year after submitting. The long wait, followed by the eventual disappointment—years ago, I would have been crushed. But such is the pact that I have willingly entered, that is:

It is easy to let this waiting room become a place of paralysis, where the fear of rejection looms large. But I have learned that this waiting must find me writing. For when the letters from editors inevitably start to pour in, it is writing that anchors me.

The rejections, when they come, are not the end of the story. They are simply part of the process.

6.

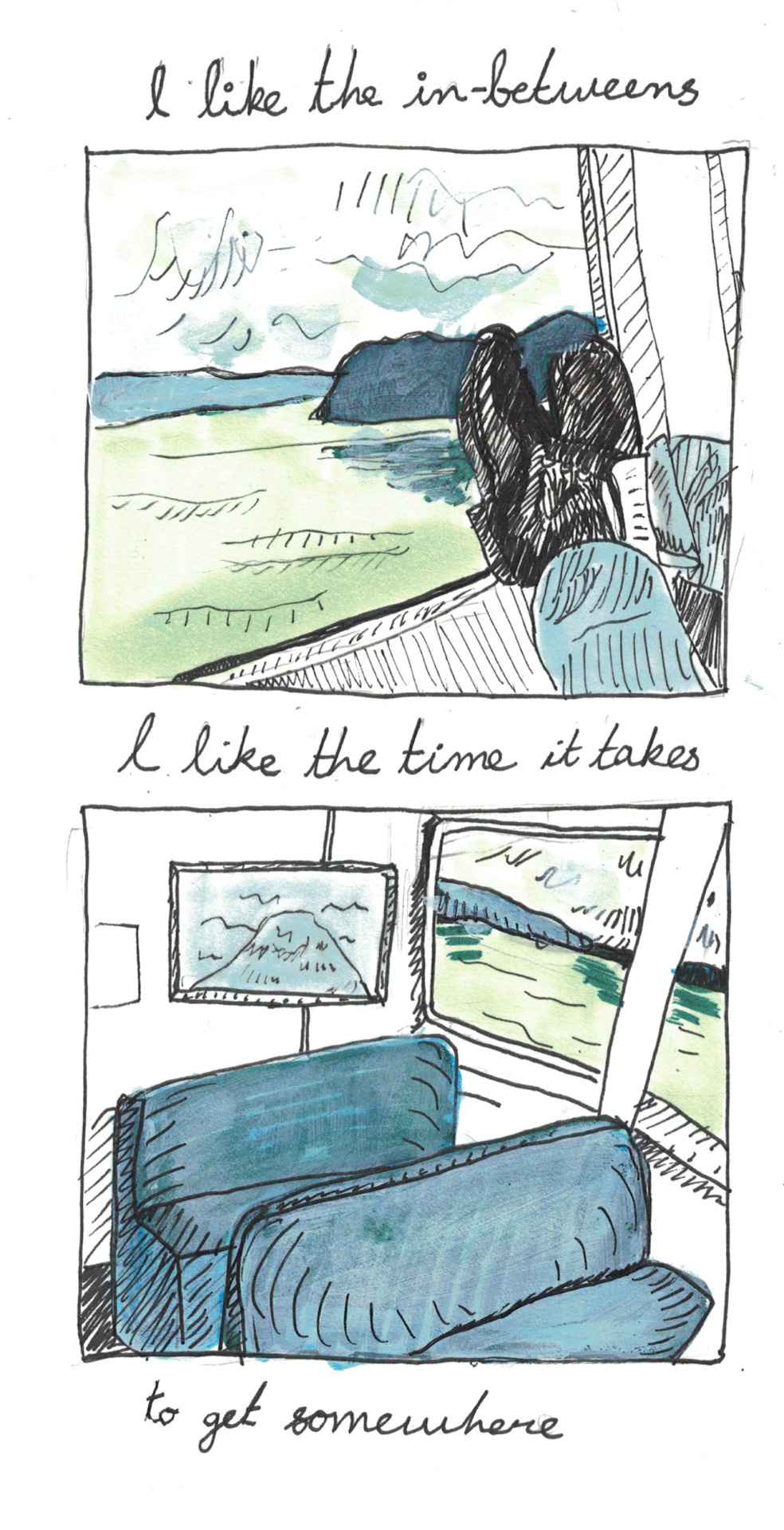

In the in-betweens, when I’m writing in my head as much as I am writing on the page, I keep a notebook where I collect ideas, observations, a smattering of found language. It is a quiet exercise, one that requires no immediate action, only attention.

Overheard something during commute, an interesting turn of phrase? I write it down. Observed something from my balcony? I write it down. Some of these may take weeks or months to germinate, while others might remain dormant forever, never able to reveal their full form. That’s fine. The act of recording all of it is as important as the writing.

Here’s a writing prompt:

Take a moment to recall the last time you found yourself in a waiting room—a space defined by its in-between nature. It might have been a doctor’s office, an airport lounge, or even a metaphorical waiting room in your life where you found yourself suspended between one moment and the next.

Write about that experience. Pay attention to the details: the sounds, the smells, the subtle movements of those around you. What were you waiting for? How did waiting affect your thoughts, your emotions, your sense of time? Explore the physical and psychological space of the waiting room, and consider what this moment revealed to you—about yourself, about the situation, or about the nature of waiting itself.

7.

There is a life to be lived in the waiting.

Waiting is often seen as an obstacle, something to be endured. But I have come to see it as a gift that allows us to deepen our understanding, to connect more fully with our work and with ourselves.

If you find yourself waiting—whether for inspiration, for the right words, or for a response—let it be a part of your process, a part of your practice. Trust that in the waiting, there is growth, there is understanding, there is grace.

Finally, a poem:

Wait

Galway KinnellWait, for now.

Distrust everything, if you have to.

But trust the hours. Haven’t they

carried you everywhere, up to now?

Personal events will become interesting again.

Hair will become interesting.

Pain will become interesting.

Buds that open out of season will become lovely again.

Second-hand gloves will become lovely again,

their memories are what give them

the need for other hands. And the desolation

of lovers is the same: that enormous emptiness

carved out of such tiny beings as we are

asks to be filled; the need

for the new love is faithfulness to the old.Wait.

Don’t go too early.

You’re tired. But everyone’s tired.

But no one is tired enough.

Only wait a while and listen.

Music of hair,

Music of pain,

music of looms weaving all our loves again.

Be there to hear it, it will be the only time,

most of all to hear,

the flute of your whole existence,

rehearsed by the sorrows, play itself into total exhaustion.

Yours,

T.

— Poet’s Field Notes, Log #004, recorded on 28 August 2024, from Manila.

Thank you for being here. I am deeply grateful for your continued readership. If you find value in my work and would like to support it, you can make a one-time donation or gift a monthly subscription via Ko-Fi. The Substack subscription model (using Stripe) isn’t available in my country, and so your support on Ko-Fi would mean the world to me. This allows me to spend more hours on what I love most: poems, and more poems.

Hello ma’am. This is beautiful and has touched me in the deepest depths of my marrow. The concept of waiting room piqued my interest. I’ve also introduced it with my friends and therapist. It’s a concept that I’ve conjured while I was in the between of job hunting. So, it was nice that there were other people who also had that same idea and experience. I like the writing exercise you put at the end. I’ll think about how my waiting room would be like.

This is wonderful! Thank you!