Dearest,

1.

I used to have a worn pair of slippers that I inherited from my father. I wore them for as long as I can wear them. The soles are thinning, one of them has a scratch from where I accidentally stepped on something sharp, and the left one insists on flopping slightly to the side when I walk. I have others—ones without battle scars—but I always reached for these until they had finally disintegrated.

I suppose it wouldn’t surprise anyone that I am drawn to those that are softened by use, worn but familiar—they tether me to the here and now when everything else feels uncertain.

The past month has been rough, personally and in the world. But then again, when has it not been? It feels like we are all caught in an endless cycle of loss, almost coming apart at the seams. And yet, even in the middle of grief and rage, I find myself moored by a pecan brownie, slightly burnt at the edges. My electricity bill, which I should absolutely pay by the end of the week. Lemon tea packets from Oman, sitting on the kitchen counter on top of the big red tub of rolled oats.

These are not impressive. But they carry the weight of a hundred small moments—proof that I am still here, still moving through the days.

Lately I have been thinking about what we are told to be captivated by—what gets to be called beautiful and what is deemed worthy of being seen. We are nudged by advertisements, by well-lit storefronts, by the quiet pressure of social expectations—and are convinced that our lives exist only in the big moments: the latest promotion, the extravagant trip to Paris, the great love story.

But I have lived long enough in a place where love means a plastic container of home-cooked kare-kare, or a bouquet of screwdrivers.

So what then of a pair of slippers? Perhaps the question is not whether an object is small or great, but whether we allow ourselves to see it. It is dangerous to assume that our lives begin only in grand gestures—I feel that the world is not divided into what is great and small, but into what we choose to be conscious of and what we let slip away.

2.

Pablo Neruda wrote odes to spoons, tomatoes, yellow flowers. For him, poetry was a way of sanctifying the everyday. He understood that what we use without thought are often the things that shape our lives the most.

Here was a man who could undo you in a single line, who wrote of love in a way that made your heart feel like an open wound—and he spent an inordinate amount of time writing about not gold or cathedrals, but onions, and chairs, and a bar of soap:

“I love

all

things,

not because they are

passionate

or sweet-smelling

but because,

I don’t know,

because

this ocean is yours,

and mine:

these buttons

and wheels

and little

forgotten treasures……O irrevocable

river

of things:

no one can say

that I loved

only

fish,

or the plants of the jungle and the field,

that I loved

only

those things that leap and climb, desire, and survive.

It’s not true:

many things conspired

to tell me the whole story.”— Pablo Neruda, from “Ode to things”

When I see someone scrolling past their own life, waiting for something more—I want to shake them. Don’t you see? The spectacular is already here.

And this might sound too earnest—but if empires have always sought to elevate the imperious and dismiss the humble, then musn’t the poet do the opposite? What of salt, what of a hairbrush, what of coins in someone’s pocket? What of the lone sock that somehow outlives its partner? I yearn to write about these because they are worthy.

And so in an era where attention is currency, what do you see when you look at a rusted key or an old pair of underwear with a loose thread? How do we assert that the mundane is still worthy of wonder?

3.

The ordinary becomes extraordinary not by magic but by the way we choose to see it. In other words, there is no secret trick. There is only presence. There is only learning how to be alive in the life you already have.

But not everyone has had the privilege of calling the ordinary art.

Wordsworth and the Romantics have long centred white, rural existence as a window into “universal human nature,” positioning their vision as reflective of a common truth.

But who gets to define the universal? And whose ordinariness is allowed to be art?

Poets of colour have long challenged these traditions, rejecting abstraction in favour of specificity. For example:

Ross Gay’s poetry and essays revel in small, tender moments. He describes joy existing in the smallest acts of care. A fig tree, for example, in his poem To the Fig Tree at 9th and Christian, becomes a site of collective generosity and reciprocity in a society marked by systemic violence.

Natalie Diaz’s work resists the tendency to abstract Indigenous experience into mere metaphor, locating intimacy even in the bend of a lover’s elbow.

Meanwhile, Ocean Vuong finds beauty in the work of his mother—elevating what has long been dismissed as invisible labour into a site of love. His poem, “Amazon History of a Former Nail Salon Worker” turns an online shopping list into an elegy.

For Camille T. Dungy, gardening is an extension of motherhood, history, and stewardship—it is an act of lineage.

Ada Limón finds awe in fleeting details, such as a dog eating snap peas. “I can’t help it. I will / never get over making everything / such a big deal,” she writes.

Danez Smith reimagines a neighbourhood as a space for mythmaking, challenging Black community stereotypes: “the little black boy / on the bus with a toy dinosaur, his eyes wide & endless / his dreams possible, pulsing, & right there.” Through Smith’s lens, Black joy, imagination, and possibility become intentional counter-narratives to the idea that Black life is only worthy of documentation when it refers to suffering.

Victoria Chang used the obituary form to mourn not just personal losses but also of everyday things: “I think about writing as freedom, the only thing I can have any say in.” Even grief, in her hands, becomes an assertion of presence.

By centering the quotidian, these poets reclaim the right to shape what is seen and remembered. They show us that language itself is an inheritance—something we pass down, something we shape, something we fight to keep. As Audre Lorde reminds us: “The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product we live…”

To notice is to bear witness. To write is to refuse erasure.

4.

Leonard Cohen once said, “If I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often.” Which is exactly how I feel when it comes to every decent idea I’ve ever had. If I knew where they came from, I, too, would set up camp there—possibly with a strong Wi-Fi signal and a never-ending supply of snacks.

That’s what’s maddening: creativity cannot be summoned on command. It isn’t a factory I can clock into. It won’t appear just because I’ve blocked out my calendar. And it won’t be bribed with a fresh notebook or a meticulously brewed cup of tea (I have tried).

Instead, ideas arrive unannounced—mid-shower, while vacuuming, in the middle of scheduling a dentist appointment. The real work, I think, isn’t willing these into existence but making space to receive when they arrive.

Because the material is already here—in the crumpled foil of yesterday’s chocolate wrapper, in the dust settling on the forehead of the wooden cat totem on my desk, in Jo’s cross-stitching of a jar of kimchi. To receive is to accept that the world is already offering us all we need—if only we are paying attention.

Poets, painters, sculptors, and designers have shown me this time and time again—the potential to be transformed:

Leo Sewell, an assemblage artist, constructs figures out of what’s discarded—toys, utensils, machine parts. What was once overlooked is now part of a larger whole. His sculptures remind me of what we cast aside without thought.

Gu Wenda turns hair and glue into large-scale installations. In his hands, these biological materials—what we shed without thought—become art, raising questions on identity and belonging. His work asks: what are the remnants of ourselves that we leave behind? What is still carrying our story?

Paul Smith practices what he calls “lateral thinking”—the ability to see an object for more than its original purpose—using bicycle handlebars as inspiration for furniture: “I hope that I’m child-like in my approach to life and my work. I think in being child-like, as opposed to childish, you have that openness and you’re very curious.”

And then there’s Shira Erlichman, poet, musician, artist—and one of the loveliest humans on earth I’ve ever had the pleasure of knowing. I return to her noticing practice over and over again. In last January’s In Surreal Life session, she said: “It is incredibly potent and fun to create…I don’t have an interest in asserting, I have an interest in uncovering.”

I mean—wow. Yes. I love how she advocates for trusting the art-making process—for just letting the poems arrive.

She shares 20 questions that I feel are meant to sharpen our awareness, to turn the smallest details into doorways for thought:

“& So I want to offer some questions to you, questions to be more fully alive inside, questions that are specific & abstract & wild & clunky & strange, questions that might guide your noticing this very day, or over the next hours, or just in the next moment…Life is noticing, after all. Really, what is life without noticing?”

This, I think, is at the heart of creation—not force, not control, but openness. It is a deep listening to the life we are already living.

5.

In my country, people find ways to celebrate despite our circumstances. It is both inspiring and acutely problematic. Filipino resilience is a testament to our strength as well as a symptom of a system that asks too much of us. But that’s a discussion for tomorrow.

What I mean is—somewhere in my neighbourhood, plastic chairs can become thrones in living rooms. A single piece of fabric transforms depending on someone’s need: today a skirt, tomorrow a curtain, or a headscarf, or a baby’s blanket.

On my father’s desk I see the last note my grandfather wrote before he died—more chicken scratch than handwriting, scrawled from a hospital bed. My father had it framed.

Objects carry memory. They outlive us. But we are taught that what is old or unremarkable is without value—that what is disposable should be disposed of.

The Japanese has this concept of wabi-sabi—the beauty found in imperfection and the appreciation of the almost-broken. For example: the way a crack in a ceramic bowl speaks of its past, the way a faded photograph still holds the shape of someone’s face.

It is a way of seeing that rejects perfectionism and expendability, understanding that time leaves its marks.

Across civilisations, the value of everyday things is not in their material worth but in what they carry and how they endure. The ancient Egyptians revered items like the ankh and scarabs, believing them to be conduits of protection and eternal life. In Mesopotamia, ziggurats housed relics—they bridged the human and the divine, the past and the present.

Even in modern spiritual practices, material symbols retain their power. In Native American traditions, ceremonial tools and personal heirlooms are imbued with ancestral knowledge. Across Asia, prayer beads, incense burners, and offerings of rice and fruit serve as connections between the physical and the sacred.

But what happens when modernity strips these objects of their meaning?

Today, artifacts are displayed behind glass cases in museums, severed from their original context. The Western, secular approach to materials often asks: What was this used for? But within spiritual traditions, the question is different: What does this still hold? There is an ongoing tension between preservation and significance—whether to see these relics as historical curiosities or honour them as living parts of culture.

6.

It is strange and terrible to live in a world that claims your life must be sensational to matter. That your worth is measured in milestones, that your story is only worth telling if it is drenched in suffering or triumph—preferably both, with a three-act structure and a neatly resolved ending.

But what if to simply exist is an act of defiance?

This crosses my mind when I see an old woman on the street laying out dried fish with a precision that could rival any gallery installation. Or when I hear my neighbours laughing at radio gossip, the sound carrying through the thin walls. Or when I make myself coffee in the morning, choosing my favourite spoon—not because it is the best spoon, but because it is mine.

We inherit what is tangible. But also—the language of our mothers, lullabies half-remembered, our childhood names.

For those of us whose histories have been fractured—by colonisation, by migration, by forced forgetting—there is a particular kind of power in choosing to keep what we are told is replaceable.

Too, there is a kind of expectation—especially for those of us whose antecedents are marked by struggle—that our stories must always be heavy. That we must write of injustice and inequity. And we do. Because we must.

But to insist on joy—to write about my beloved picking up fallen coconuts in the backyard or humming while folding the laundry—that is where I place my devotion.

7.

When I say that I have been radicalised in my way of noticing, I mean that Angel Nafis has rewired the way I see the world.

More than five years ago, I heard her speak on what it means to observe and I haven’t been the same since. Franny Choi, one of the hosts of the VS Podcast together with Danez Smith, summed the whole poetics as this: “Looking is praising.”

Angel discussed how poets of colour are often steered toward the pastoral and the non-specific—as if writing from our realities is excessive, as if race and identity must be abstracted and made digestible: “Stop talking about who you are. Talk about some shit that everyone can relate to. Like this deer.”

I laughed when I heard that. And then I felt my chest tighten. Because isn’t that how it all works? Obliterate the particulars of your experience so it can fit into a narrative that feels familiar and safe. So that the reader doesn’t have to work too hard. So that your poem doesn’t make anyone uncomfortable.

The truth is, I do not have deer in my life.

I have stray dogs on street corners, tails flicking against metal gates. I have motorbikes weaving through traffic, the smell of gasoline and sweat and heat. I have the sound of someone selling taho in the morning, voice echoing between houses.

Again and again, I’ve heard that these things—my things—are too small, too niche, too personal to be poetry. But I know now that I do not have to justify my own witnessing to anyone.

Angel also explored how, traditionally, nature in poetry has been a stand-in for the unanswerable: when you do not know what to say, when you reach the edge of language, you turn to the vastness before you.

There is no human answer to love—but there is a river.

There is no human answer to grief—but there is the sky.

Yet she challenged the assumption that nature is the only place we can turn: “I turn to a smallness that to me represents a bigness.” Which hit me like a brick to the face. Because yes.

This is what I have always known in my bones. When I do not have an answer, of course there is the sea. But there’s also my sister’s hands peeling a ginger by the sink. There’s the lone cockroach on its back, feet wriggling. My bigness is in the smallness of the day-to-day.

At some point in the podcast, Angel asked questions that has been rattling in my head ever since: “Is spirituality just specificity and noticing? Is telling the truth spiritual? Is that all it is? Just…not lying?”

Maybe what I am doing—what all poets are doing—is not so different. Maybe poetry is just another form of gratitude—a way of saying: thank you for letting me see this.

Too, there is the urgency to write things down before they disappear. The moment you describe the bird, the bird is already gone. The moment you describe a feeling, the feeling is already something else.

Since stumbling upon this episode so many years ago, I have been ruined in the best possible ways. What do I see? A half eaten donut dusted with powder milk. An electric socket that looks like a face. A pair of earrings left on the bathroom counter, tangled together like vines.

I cannot unknow the truth of the smallest things—that they can hold entire universes.

Ah, dear reader, all of this to say—I am trying to capture the moment before it disappears. Because there is too much to notice and I want to notice all of it.

8.

We are all born looking—staring at what we don’t understand, asking questions with no answers, pointing at the moon. And then, little by little, we are trained to stop. To focus. To be practical. To keep our heads down.

That being said—we can always begin again. Here are a few ways:

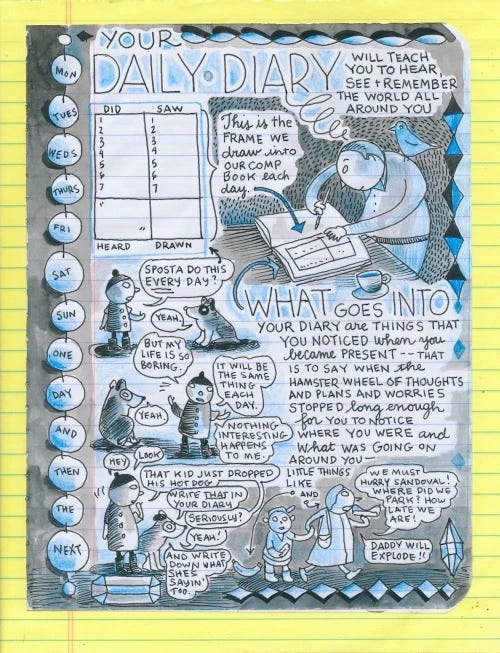

I recommend Lynda Barry’s Daily Diary Exercise:

Every day, make a quadrant in your notebook and label them Did, Saw, Heard, and Drawn. Fill them up. It doesn’t have to be exhaustive. It can be “ate an entire bag of chips” / “saw a dog wearing a sweater” / “heard a kid singing off-key” / and then a doodle of a rooster.

The point is not to document meaning—the point is to document at all.

Meghan also introduced me to Linda Gregg’s 6 Things:

“I am astonished in my teaching to find how many poets are nearly blind to the physical world. They have ideas, memories, and feelings, but when they write their poems they often see them as similes. To break this habit, I have my students keep a journal in which they must write, very briefly, six things they have seen each day—not beautiful or remarkable things, just things. This seemingly simple task usually is hard for them. At the beginning, they typically “see” things in one of three ways: artistically, deliberately, or not at all. Those who see artistically instantly decorate their descriptions, turning them into something poetic: the winter trees immediately become “old men with snow on their shoulders,” or the lake looks like a “giant eye.” The ones who see deliberately go on and on describing a brass lamp by the bed with painful exactness. And the ones who see only what is forced on their attention: the grandmother in a bikini riding on a skateboard, or a bloody car wreck. But with practice, they begin to see carelessly and learn a kind of active passivity until after a month nearly all of them have learned to be available to seeing—and the physical world pours in. Their journals fill up with lovely things like, “the mirror with nothing reflected in it.” This way of seeing is important, even vital to the poet, since it is crucial that a poet see when she or he is not looking—just as she must write when she is not writing. To write just because the poet wants to write is natural, but to learn to see is a blessing. The art of finding in poetry is the art of marrying the sacred to the world, the invisible to the human.”

And here are two exercises I think might be interesting to try:

The ordinary inventory

Keep a journal where you list all everything mundane that catches your eye.

Don’t overthink it. Just note it down.

Be unprecious. Keep it as you would a grocery list.

There’s a reason we keep inventories. They are, at their core, records of what exists. By keeping track of what you see, you are creating a catalog of attention. You are telling yourself that you were here—that you were awake to your own life.

The longer you keep the practice, the more you begin to see patterns—what keeps catching your eye, what you return to again and again. Maybe it’s always light filtering through curtains. Maybe it’s always the sound of footsteps on wet pavement. Maybe it’s always the colour yellow.

The morning object meditation

Pick one object from your surroundings each morning and spend five minutes writing.

What does it feel like? What does it remind you of? What history does it carry?

You don’t have to look harder. You just have to look longer.

You hold a key in your hand and ask: Who else has touched this? What doors has this opened? What doors will it never open again? You pick up a lemon and ask: Where did this grow? Who picked it? Who carried it? How many hands did it pass through before arriving in my kitchen?

9.

It feels impossible—selfish, even—to speak of the sacrosanct when we have become bystanders to the ongoing genocide. I echo Fatima: “I want to sing about joy but there’s so much to be mad about.”

The homes in Gaza, filled with the same everyday things—kitchen tables where family stories were told, beds that used to cradle children who will now never grow up—are all waiting for a tomorrow that may never come.

But it is precisely because of this that I must pause and recognise: what is happening in Palestine is not just the destruction of buildings, but a deliberate erasure of people. And still, there is resistance. There is survival. There is the undeniable, unwavering right to exist—and to live.

To hold onto a cup or a book is a refusal to forget. A declaration that home, however fractured, still exists in whoever carries its memory.

I will continue to hope and believe that one day, every displaced person will return home. That one day, Palestine will be free.

10.

What have you noticed today? Look around you. What is it trying to tell you? Write it down. Share it with me. I would love to hear from you.

And for some further reading—

If this essay resonated with you, here are some books and collections that explore poetry as witnessing, joy as resistance, the everyday as miraculous:

Pablo Neruda, Odes to Common Things

Ross Gay, The Book of Delights and Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude

Natalie Diaz, Postcolonial Love Poem

Ocean Vuong, Time is a Mother

Camille T. Dungy, Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden

Ada Limón, The Carrying and The Hurting Kind

Danez Smith, Bluff and Homie

Victoria Chang, Obit

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider

Leonard Cohen, Book of Longing

Shira Erlichman, Odes to Lithium (and her Substack, Freer Form)

Angel Nafis, BlackGirl Mansion

Dinah Lenney, The Object Parade: Essays

Leonard Koren, Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers

Lynda Barry, Syllabus

Rob Walker, The Art of Noticing (and his Substack)

Amanda Machado, “How Writers of Color Are Changing What Nature Writing Looks Like”

Ross Gay on the insistence of joy (On Being)

Finally, a poem:

Night Bird

Danusha LamerisHear me: sometimes thunder is just thunder.

The dog barking is only a dog. Leaves fall

from the trees because the days are getting shorter,

by which I mean not the days we have left,

but the actual length of time, given the tilt of earth

and distance from the sun. My nephew used to see

a therapist who mentioned that, at play,

he sank a toy ship and tried to save the captain.

Not, he said, that we want to read anything into that.

Who can read the world? Its paragraphs

of cloud and alphabets of dust. Just now

a night bird outside my window made a single,

plaintive cry that wafted up between the trees.

Not, I’m sure, that it was meant for me.

Yours,

T.

I stumbled upon your field note this afternoon, and I am smitten. I can't wait to catch up on all your other field notes. Your storytelling is riveting. You unraveled provocations. Thank you for writing this.

My 6 things from this morning:

A girl on a scooter clutching her mothers kurta

3 chairs marked “fragile artefact” in prime public view and I thought me too

A tiny scratch on the back of my neck; reminder of my first-time-ever in life long nails that I’m wildly unprepared for

The breadth that OAFF takes to start the first line of NEU: https://music.youtube.com/watch?v=WG4ba8HF_lM&si=bqR5C5o_sHwVqsIc (that I have heard on loop 8 times this morning)

The length of NEU being <2 minutes and it feeling impossible to hear it enough

If I like something or someone, my immediate need to find a resemblance of them to someone else I love