The asking itself is the practice

Manifestos, maybes, and making space for multiplicity

Dearest,

1.

I have always been more interested in questions than in answers. I find that they feel like a way of staying in motion—of staying alive. A good question makes me want to write—to follow it wherever it wants to go.

I've been collecting questions the way some people collect shells or smooth stones—each one a small treasure, imperfect but potent:

How does my writing make space for what is unspoken?

Where does my grief live in my work? Where does my joy live?

How do I create a rhythm that feels true to the way I think, feel, and remember?

These questions have become my compass, more reliable than any answer I've ever been given about how to write, what to write, or why writing matters.

In workshops and literary spaces, I've noticed the usual refrain: Write what you know. Show, don't tell. Kill your darlings. These dictums circle endlessly, handed down like heirlooms we're meant to cherish, unquestioned.

But what happens when you come from somewhere else—when your relationship to language is marked by a history of being conquered, when your body carries stories that don't fit neatly into the usual narrative arcs, when your experience of time itself spirals rather than marches forward? What happens when you're asked to kill your darlings, but your darlings are the very things keeping your ancestors alive on the page?

You begin to question. Not just the rules of craft, but the assumptions underlying them. Not just what makes “good writing,” but who decided, and why, and whether their vision of goodness has room for the way your tongue navigates English—a language that arrived in your homeland on ships, alongside guns.

For a long time, I thought that to be taken seriously, I had to sound like I knew what I was talking about. I had to prove that I was not lost, even when I was writing from grief, contradiction, or fracture. If I ask about anything, I reveal my hand. But the older I get, the more I’ve come to understand that the asking itself is the practice.

Questions, I've found, are not merely the pathways to answers. They are creative acts themselves—spaces that open up inside us and between us. A well-formed question contains worlds within it. It makes room for what has not yet been imagined. It invites possibility rather than foreclosing it.

To ask a question—especially one that has no easy answer—is to assert the right to complexity. That is, to make space for doubt and what hasn’t yet been spoken.

Recently, I was part of The Seventh Wave’s Narrative Shifts digital residency—and one of the things that have stayed with me was the idea of honouring the question.

It made me think of how developing our own questioning practice might transform not just what we write, but how we exist as writers in a world that so often demands certainty where there is none.

I want to trace the questions that shape my own writing life—from the personal to the political, from the bodily to the archival.

How do questions manifest in our work as artists? What happens when we treat the unknown not as a deficiency to overcome, but as the very soil from which our most honest work might grow?

2.

In the environment I was raised in—a postcolonial, Catholic, patriarchal Philippines, where survival often depends on obedience—questions were seen as impolite at best, dangerous at worst. You do not question your elders. You do not question the Church. You do not question tradition, especially if that tradition is draped in silence.

The questions I learned to ask early were internal ones, whispered ones, hidden in the margins of my notebooks:

Is it okay to feel this?

Why doesn’t this version of the story include me?

What happens if I say no?

The project of the empire is, among other things, a flattening of narrative. It insists on one history, one language, one “rational” worldview. It rewards answers that align with power. It teaches us to mistrust the things that cannot be measured, proven, or simplified. But questions—real ones—refuse that. They disrupt. They insist on more. They crack open the illusion of singular truth.

Too, the history of colonisation is, in many ways, a history of answers imposed upon questions never asked. It is the story about who is civilised and who is savage, about which languages matter and which are primitive, about whose stories deserve to be canonised and whose can be forgotten.

Questioning, then, becomes an act of resistance—especially when you have been historically denied the authority to ask. It is to make room for other ways of knowing: the ancestral, the embodied, the speculative, the spiritual. It is to say: what I know may not be legible to you—but that does not mean it is not knowledge.

When I ask:

How do I write myself into a lineage that is both inherited and chosen?

—I am refusing the notion that my literary forebears must all speak English, must all have been educated in Western institutions, must all have shaped their sentences according to dominant aesthetics. I am making space for the oral storytellers in my family whose names I'll never know, for the women who whispered stories between chores, for the gossip and the ghost tales, for the songs that are woven in griefwork, for the myths that weren't written down because the people who told them weren't considered worthy of documentation.

To ask rather than declare is to acknowledge that we don't yet know everything, that we are still becoming, that the boundaries between categories might be more permeable than we've been taught.

3.

There’s a reason why so many of us who are women and nonbinary, who are brown or black, who are disabled, who write from the “global south,” are often pushed into writing that explains, that educates, that translates. We’re asked to clarify, not complicate. We’re asked to provide context, not texture. But what if we refused that role? What if we wrote not to explain, but to wonder?

What if the question is the text?

I think of the times I've sat in classes and workshops where I’ve been told: “Readers will not understand this,” as though that could only ever mean white, Western, English-as-first-language readers. As though my primary responsibility as a poet was to make myself legible to those who have never had to work to understand anyone different from themselves.

What if, instead of asking:

How can I make myself understood?

I asked:

What happens when I refuse to translate certain parts of myself?

What if, instead of apologising for my difference, I questioned why sameness is so prized in the first place?

Questions allow us to shift from defending our existence to investigating the systems that require such defence. They move us from the position of being questioned to the position of questioning.

Here’s something I’ve been circling lately:

How do I write as a self that is not singular but polyvocal, fragmented, and shifting?

I think I’ve been asking it my whole life.

The literary education I was given—at least formally—was shaped mostly by American canon. This hangover still lingers in the school curriculums today. English is praised not just as a skill, but as a kind of social mobility. I learned to write in a language that was never mine, yet became the one I know best.

But I’ve also been assembling another lineage—one that includes poets of colour, poets who make language stutter and burn and pray. This is what I’ve been doing for nearly twenty years with Read A Little Poetry—re-educating myself, choosing whom I want to read and be obliterated by.

I claim this literary genealogy for myself. It is gathered slowly and built through the act of asking:

Who came before me?

Who do I write beside?

What ghosts are in my mouth when I speak?

4.

The questions we ask shape the stories we can tell. And in a world built on accounts that have defined some of us as peripheral, as minor characters in someone else's heroic journey—asking different questions becomes essential to writing ourselves into existence.

How do I write as both witness and participant?

This question acknowledges that I am not an objective observer of my culture, my history, or my lived experience. I am embedded within them, shaped by them even as I shape them through my writing.

It rejects the fantasy of the neutral observer and instead embraces the messy reality of being both subject and chronicler, both the watcher and the watched.

Our questions need not be answerable to be valuable. In fact, some of the most generative questions are those that resist closure, that continue to unfold the more we sit with them. They are invitations rather than investigations—doorways that open onto further doorways, leading us deeper into the entanglement of being alive.

Today, when I sit down to write, I begin not with certainties but with curiosities. And in doing so, I find myself creating work that feels truer to my experience of a world that isn't waiting to be explained, but to be explored, questioned, wondered at, and loved in all its beautiful, unresolvable mystery.

That’s what questions make possible. Not perfect answers, but the space to say: I don’t know, but I am here, and I am looking.

5.

Which brings me to manifestos. Those delightfully bombastic declarations of intent that make the average Facebook status update look positively understated.

For centuries, writers and artists have been penning these literary battle cries, essentially saying: HERE'S WHAT I BELIEVE AND I'M ABSOLUTELY CERTAIN ABOUT IT AND ALSO I'M SHOUTING.

On one hand, I admire their clarity—the boldness of this I believe or this I reject. On the other, they often sound like they were written by someone who has never second-guessed a single thing in their life. Which, frankly, I cannot relate to.

Imagine having that kind of certainty! Me, I can barely decide what to order for lunch without drafting a comparative essay on the relative merits of soup versus sandwich. (Current tally: sandwich is more portable but soup feels like a hug in a bowl. The debate continues.)

Historically, manifestos have had two moods: disrupt-the-establishment or become the establishment. Sometimes both, in quick succession. They have been the domain of those who have—or at least believe they have—the authority to make sweeping pronouncements about art, literature, and existence itself.

But for every manifesto that split open a form, there’s one that is privilege dressed as rebellion. And often, the loudest manifestos in the room belonged to men—primarily written by men, primarily white men, primarily white men who enjoyed starting sentences with phrases like “We declare that...” and “The time has come to...” Not exactly a tradition that screams inclusive.

And yet, there's something powerfully seductive about manifestos. They offer clarity in a foggy world. They create community through shared vision. They reject tepid middle grounds in favour of bold stances. These are not small gifts.

The question becomes: how do we engage with this tradition without reproducing its exclusions? How do we claim the power of declaration without falling into the trap of universal pronouncements that erase difference?

One answer might be found in looking at how writers from marginalised communities have transformed it.

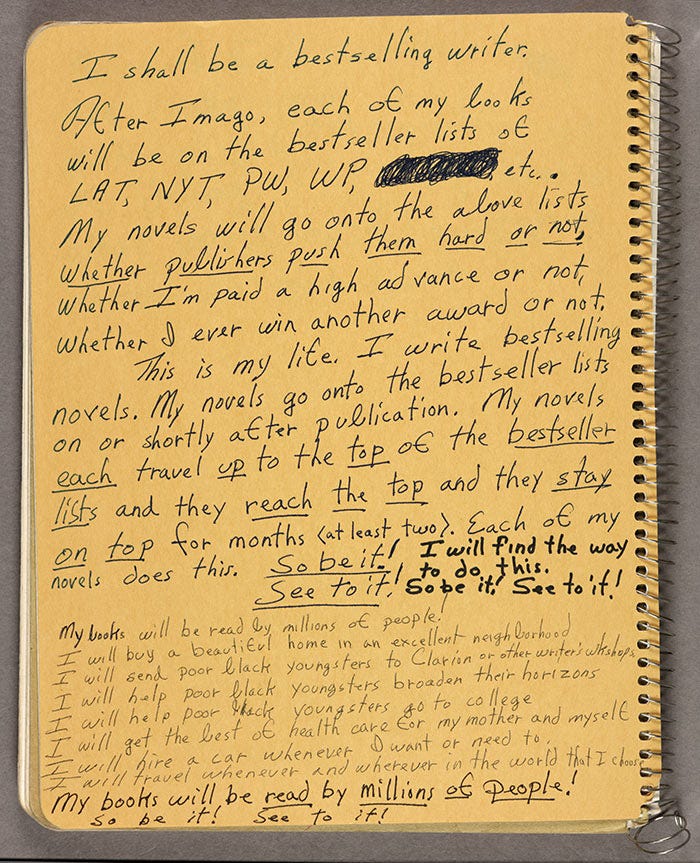

Take Octavia E. Butler's “Essentials of Success”—it’s not even labeled a manifesto, but I consider it one. It’s a list that became a life’s ethos.

Some of the things she wrote were: “Tell stories filled with facts. Make people touch and taste and KNOW.” It centres connection rather than disruption, communication rather than provocation.

One of my favourites is where she writes:

“I shall be a bestselling writer...I will find the way to do this. So be it! See to it!”

There's something heart-stoppingly vulnerable about this woman commanding herself toward success in a field that actively excluded people who looked like her. It's not addressed to the world—it's addressed to herself. It's not saying “Here's what art should be”—it's saying “Here's what I will make of myself.”

I think it’s a radical act of a woman writing herself into a future she had to imagine before anyone else could.

6.

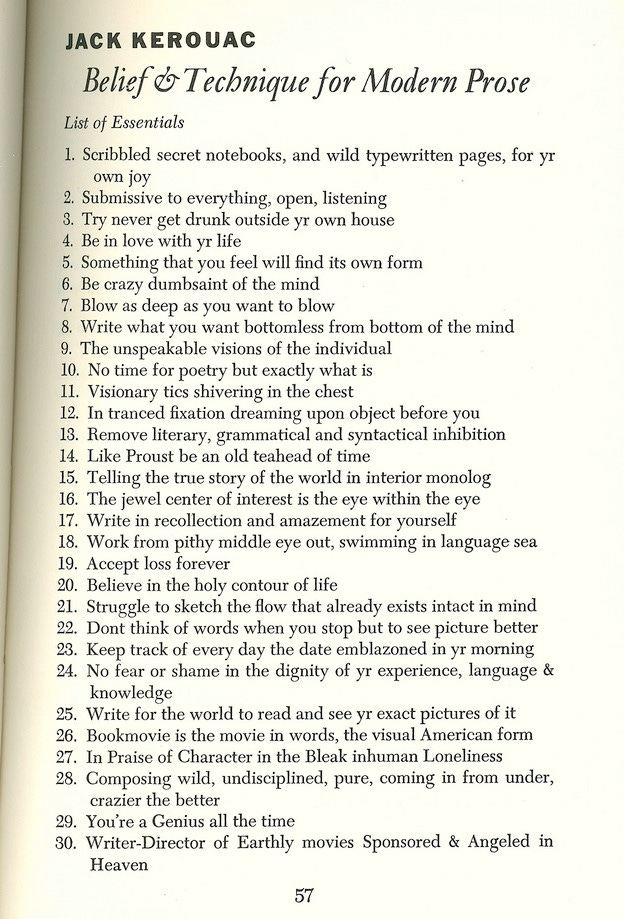

Compare this to Jack Kerouac's “Belief & Technique for Modern Prose,” with its thundering imperatives: “Scribbled secret notebooks, and wild typewritten pages, for yr own joy” and “Remove literary, grammatical and syntactical inhibition.”

Kerouac's manifesto vibrates with a particularly American brand of masculine freedom. Just let loose, man! Write wild! Don't think, just BE!

It's the literary equivalent of a road trip movie where no one has to worry about who's watching the kids or paying the bills or whether it's actually safe to hitchhike as a woman.

When Kerouac declares “Be crazy dumbsaint of the mind,” I can't help but think about who gets to be crazy in public without consequences. Certainly not women writing from psychiatric institutions. Certainly not immigrants whose sanity is perpetually questioned simply for existing between cultures. The freedom to be wild, undisciplined, and unedited is a privilege not evenly distributed.

Kerouac’s text reads like the diary of someone who drank five cups of coffee and decided to invent a religion:

2 - Submissive to everything, open, listening

10 - No time for poetry but exactly what is

19 - Accept loss forever

And yet—I confess a certain fondness for Kerouac's exuberance, his breathless insistence on the value of spontaneity and passion. I admire the chaos of it. I really do. It’s thrilling in that manic, typewriter-on-the-lap-in-the-bathtub way.

But it also reeks of a particular kind of freedom—the freedom to be in the muck and call it genius. The freedom to never explain. The freedom to declare your spontaneity as holy and not be institutionalised for it.

Which is to say: Kerouac had room to romanticise doubt. Butler had to survive it.

That contrast stays with me.

What would it mean to take what's liberating about his approach while acknowledging its limitations? What if we read his “Write what you want bottomless from bottom of the mind” alongside Butler's more measured but equally determined “I will find the way to do this”?

7.

What if manifestos, like questions, could exist in conversation rather than in competition?

In my own reading and writing life, I've begun to think of manifestos not as absolute truths to follow, but as provocations to think with, to write against and alongside, to draw energy from when my own well feels dry.

I read them as historical artifacts that tell us something about who had the confidence to make declarations in different eras, and what those declarations reveal about the anxieties and aspirations of their times.

More importantly, I've started to see the connection between my questions and the promise of arriving at my own manifesto—not one that would tell others how to write or create, but one that would clarify for myself what matters most in my work. A personal doctrine of creation that acknowledges where I've come from and gestures toward where I might go.

Because if questions are openings, manifestos are trajectories—directions we might move in once we've made space for ourselves on the page. They need not be fixed or final. They can be revisable declarations, certainties held lightly, proclamations that remain open to question.

Maybe the best manifestos are those that leave room for questions. And maybe the most powerful questions are those that might, someday, crystallise into manifestos—not absolutes, but moments of clarity amid creating.

So yes—I want to make room for questioning, where you do not arrive with a megaphone, but with a lamp. The kind that lights a small circle and says: Here. This is where I begin.

8.

I used to have so many preconceived notions about being a poet when I was much younger. I imagined it like a passport stamp: once you published a book, or got into a fellowship, or used the word ekphrasis once in conversation (ha!), you were officially allowed to speak with authority. You could stop asking questions and start delivering truths.

That moment never came. What came instead were better questions.

In the residency, we did talk about the idea of a mini manifesto. But it started not as a list of beliefs. Not as pitch. Just…questions. Internal ones (about our own process) and external ones (about what our work asks of others). This distinction creates a nuanced space for exploration. Our internal questions allow us to clarify our creative challenges, while our external questions connect us to the larger conversations our work enters into.

When I first tried this exercise, the questions poured out of me like water from a tap I couldn't—and didn't want to—shut off. I filled pages with them.

It was like creating a map of my preoccupations, my obsessions, my deepest concerns as a poet.

There were the craft questions:

How do I write from multiple selves without losing coherence?

What form best holds the emotional weight of what I’m trying to say?

How do I move through revision without severing the poem’s original pulse?

Then the harder ones:

What is my stake in this work, and how deeply am I willing to implicate myself?

How do I write about trauma without centering the wound?

How do I write joy as structure, not interruption?

And then the ones that live closest to the skin:

What am I afraid to write, and why?

What do I need to unlearn in order to write freely?

Where does language fail my body, and where does it set me free?

These questions remind me that my process isn’t just about getting something on the page. It’s about listening for where the page resists. It’s about locating the edge of what I’m allowed to say—and then writing a little past it.

But I don’t just write toward myself. I also write toward others—toward readers, imagined or real, who might be sitting with their own unspoken questions. That’s where the external questions live. Questions like:

What does it mean to be alive and to bear witness?

What happens when we refuse to be a single being?

What do we inherit, and what do we refuse to pass down?

How do we find meaning in the ruins?

What does it mean to be witnessed, fully?

These are the kinds of questions that are too big to answer, and too urgent not to ask. They’re not rhetorical, they’re invitations to read more deeply, feel more tenderly, and linger longer in discomfort, wonder, awe.

9.

Another exercise introduced in the residency was the “Maybe” list, inspired by body performer Saff Lynn Douglas’ anonymous art project, “Maybe u r like me.” We were asked to write a series of statements beginning with “Maybe,” as a means of connecting across borders of identification.

What emerged surprised me. My maybes weren't just tentative—they were hopeful, even when addressing difficult realities. My list began like this:

Maybe you’re not as bad as you think

Maybe you’re on the cusp of something good

Maybe it’s bound to happen

Maybe you are no longer in danger

Maybe you can make it happen

Maybe this is not permanent

Maybe it’s going to take as long as it takes

Maybe you are stronger than you think you are

Maybe it means your whole life

Maybe you are going to be okay

Maybe this is the season

Maybe it is what is necessary

Maybe you only have to open

Maybe hope is what threads through it all

I didn’t realise until later that these maybes were a map. Not to certainty, but to continuity. To the possibility that writing—and living—is a series of negotiations between doubt and faith.

These maybes assert possibilities without insisting on them. They open doors without forcing anyone to walk through them. They allow for agency in both writer and reader.

Think of it this way: if traditional manifestos are fortresses—solid, imposing, uncompromising—and questions are doors—openings, invitations, points of entry—then maybes are bridges. They connect the solid ground of what we believe with the open sky of what we wonder. It's a linguistic space that honours both the clarity we sometimes achieve and the doubts that keep us honest.

Crafting your own questioning practice, then, might begin with these three approaches:

(1) Internal questions that clarify your creative concerns,

(2) External questions that connect your work to larger conversations, and

(3) Maybes that bridge the gap between hesitation and declaration.

Together, they create a method that is both grounded and flexible, both personal and communal.

The beauty of this approach is that it evolves with you. The questions I was asking five years ago are not identical to the ones I'm asking today. Some have been answered, or at least addressed. Others have deepened or shifted focus. New ones have emerged from new experiences, new readings, new conversations.

A questioning practice is never static. It moves as you move, grows as you grow, changes as you change. It doesn't demand the permanence or universality of a traditional manifesto. It allows your creative process to be as dynamic and as contradictory as you are.

Because ultimately, that's what we're after, isn’t it? Not a writing practice that flattens us into certainty, but one that honours the fullness of our complexity—all our selves, all our stories, all our ways of being in the world.

And if you're thinking, “But how do I begin?”—well, you already have. The very act of asking is the beginning.

10.

Finally, a poem:

Afraid So

Jeanne Marie Beaumont

Is it starting to rain?

Did the check bounce?

Are we out of coffee?

Is this going to hurt?

Could you lose your job?

Did the glass break?

Was the baggage misrouted?

Will this go on my record?

Are you missing much money?

Was anyone injured?

Is the traffic heavy?

Do I have to remove my clothes?

Will it leave a scar?

Must you go?

Will this be in the papers?

Is my time up already?

Are we seeing the understudy?

Will it affect my eyesight?

Did all the books burn?

Are you still smoking?

Is the bone broken?

Will I have to put him to sleep?

Was the car totaled?

Am I responsible for these charges?

Are you contagious?

Will we have to wait long?

Is the runway icy?

Was the gun loaded?

Could this cause side effects?

Do you know who betrayed you?

Is the wound infected?

Are we lost?

Will it get any worse?

Celebrating & Amplifying

Sharing some recent news from friends and people I admire that you should check out—poets, artists, thinkers, and makers whose work deserves more eyes, more ears, more hearts. If you’re looking for something new to read, listen to, or witness, start here:

Cortney Lamar Charleston’s third poetry collection, It’s Important I Remember, is now available for pre-order from Northwestern University Press. I’m excited for this!

Mandana Chaffa and Mai Der Vang have a lovely conversation about Primordial: “When I write a poem, I’m also enriching language with further possibilities. I’d like to think I’m giving back to it even when I’m breaking the rules. In this way, my seeking has grown to realize I must reciprocate and allow language to do through me what it needs.”

For more than a decade, Al Filreis has taught ModPo, a MOOC that has drawn some 435,000 students from 179 countries. So excited for his book, The Classroom and the Crowd, where he reflects on his decades of experience as a founder of participatory literary communities and teacher of online courses.

Jaton Zulueta is opening AHA Sunrise, a new centre that will serve 150 public school students in Makati—please consider donating!

Ashna Ali and Divya Victor sit down with Rajiv Mohabir to discuss his poem, “Immigrant Aria,” for the inaugural episode of The Source podcast, produced by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop.

Ayokunle Falomo’s book, Autobiomythography of, has been doing the rounds. Happy for you!

Congratulations to Ajanaé Dawkins on the launch of Blood-Flex!

Also celebrating the release of the anthology, Heaven Looks Like Us: Palestinian Poetry, edited by George Abraham and Noor Hindi. As George wrote: “This is only the beginning. May this book give us all the excuses to gather, organize, grieve, create, and return. May this book LIVE in the hearts of students and activists, in the words and praxis of poets engaged in anti-colonial resistance, on syllabi in and beyond the universities who fail us.”

If you are teaching next term, consider ordering your course books through Workshops4Gaza.

Sara Matson’s microchap, Ardently, is forthcoming from Ghost City Press as part of their Summer series. Yes!

Sarena Brown is offering a 5-day Choose Your Own Adventure online art residency on May 26-30, with asynchronous check-ins and spontaneous body doubling sessions.

Yours,

T.

The openness and broadsweeping inquiry here as well as the deep-down dives make this a satisfyingly multidimensional piece that has given me courage to ask. I love how you posit a metaphorical archaeology here, where manifestos, maybes and more give us clues to what we have held on to, what we might want to let go and transform, and what could become or is in a state of becoming. They are inquiries of quality not quantity, very antithetical to Western linear, either-or thinking and it's freeing for my overly white American brain that overlays a heart that yearns to find a more human way to live and love. Thank you from the bottom of that heart for offering a bridge (love that bridge metaphor!) to new ways of exploring and reflecting. On manifestos, one that allows for flexibility and inquiry is tantalizing. I AM ALWAYS QUESTIONING IN MY SEARCH FOR GREATER UNDERSTANDING AND OPEN-HEARTED CONNECTION WITH HUMANITY AND THE WORLD AROUND ME. Trying that on for size. And heading over to Kofi.

This whole post is awesome. Thank you.