Dearest,

1.

The heat has been unbearable lately. 42°C on average, which I’m convinced is God’s way of slow-roasting us into submission. I’ve taken to staring at walls and forgetting what I was doing halfway through a sentence. My brain is soup. My ambitions are puddles. I can feel my soul evaporating through the top of my head.

Somewhere in this haze of dehydration and what I can only describe as a full-bodied existential broil, I remembered something I told myself when I turned 39:

Make decisions from your talent, not your desperation.

At the time, it felt like a minor revelation. I had just deleted three half-written emails—awkward, overeager things—trying to pitch myself for projects I didn’t want, but thought I should want. I was exhausted, and the kind of tired that makes you honest.

And like all good truths, what I said has started to gnaw at me. Because it’s one thing to swear off panic as a career strategy; it’s another to wake up and realise you have no map once you let go of fear. I’m actively trying to dismantle the old compass of my life (scarcity, urgency, grit), but haven’t yet fully calibrated the new one (desire, alignment, self-trust). Which is disorienting.

It makes different questions surface. Not what am I running from—but what am I drawn toward? Not what will keep me afloat—but what might actually root me? It’s a strange in-between—like standing in the ruins of the self that hustles from hunger vs. the self that hopes to make from wholeness.

What if the hardest part isn’t knowing what you want—but trusting that you’re allowed to want it in the first place?

So I did what I am sometimes wont to do when I’m spiralling: I picked up a book.

Specifically, Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers by Leonard Koren (Imperfect Publishing, 2008)—a book I’d meant to read for years, shelved and forgotten, like most promises to myself. I took it out for a walk, read it in one afternoon, and have been thinking about it ever since.

2.

There’s a kind of violence in being constantly required to explain yourself—especially when you’ve been raised in a country and a body repeatedly told that creativity is indulgent, that feeling too much is a liability, and that art must pay its way to be permitted.

In colonised contexts like mine, legibility isn’t just a courtesy—it’s a survival strategy. It demands conforming to dominant norms of understanding—whether emotional or linguistic (e.g. using English as default, where multilingual work is often asked to translate itself fully, justify its unfamiliarity, or footnote its mother tongue). You’re creative only if your work is recognisable, marketable, and optimised for consumption.

But legibility is never neutral. It disproportionately disciplines those whose identities and expressions have already been marked as excessive or unreadable by Western, capitalist standards.

So you learn to translate—not just language, but self. You sand the edges down so no one gets cut. You rehearse your story until it fits a format. You become a professional in your own packaging.

Much of my creative life—especially outside poetry—has been shaped by this constraint to be palatable. To polish the process. To offer something that ends. Something that earns.

And then I read this line in Koren’s book:

“Wabi-sabi is a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.”

The sentence struck me like a bell. Not because it revealed something new—but because it named something I’ve always known as a poet, but have rarely been allowed to believe elsewhere.

Here’s the thing: I already know how to live with this. As a poet, incompleteness is a practice. In poetry, I don’t finish things so much as I release them. A poem trails off, stutters open, leaves the door ajar. I trust that a line can hum with meaning even if it never reconciles.

But put me in a client meeting, or a brand strategy session, or a Zoom room with startup founders trying to “scale authenticity”—and it’s a different story. The same part of me that loves ambiguity in a poem becomes anxious in a pitch deck. The tension to be legible, persuasive, final—it clamps down hard. In those spaces, what is open-ended feels dangerous. A threat to trust, to timelines, to profitability.

Some parts of the world—especially the shiny and venture-backed—won’t let you live in wabi-sabi. They demand substantiation. So I switch languages. I clean up the mess. I wrap the idea in strategy speak. I learn to sell what I never get to feel.

To be in process too long, I’ve been taught, is to be a dilettante. A mess.

But wabi-sabi offers a different logic: that imperfection is not what you fix—it’s what you feel through. That delay is not avoidance—it’s attention. That process isn’t what you survive to get to the work. It is the work.

And when I look at my poems now—the ones that trail off, that stay with me long after I’ve abandoned them—I realise: maybe they were never meant to be finished.

Maybe I’m not either.

3.

Let’s get this out of the way: Wabi-Sabi is not a perfect book.

It’s slight. It’s meandering. It gestures more than it defines. At times, it reads like a series of Post-its stuck to the margins of an invisible thesis. And while I have great affection for things in flux (hello, entire folder of untitled .docx files), there are moments where I wish Koren had gone further—particularly around the cultural politics of what he’s circling.

He names the disappearance of wabi-sabi as a high-cultural philosophy in Japan but avoids asking why and how it disappeared. He doesn’t trace the erasure through modern Japanese history nor does he confront the West’s insatiable habit of extracting the sacred and reselling it as lifestyle.

“…[T]he preeminent high-culture Japanese aesthetic…was becoming—had become?—an endangered species.”

Endangered—or just no longer profitable?

Wabi-sabi, in its original context, is embedded in spiritual practice, material modesty, and social ritual—especially the tea ceremony, which is not about tea at all but about intentional living. Yet Koren rarely touches the discipline behind that devotion. Nor does he reckon with what it means to export a tradition steeped in Zen Buddhism into a book designed for Western artists and designers—without, ironically, examining how the global design industry often strips cultural meaning for the sake of beige elegance.

To be blunt: wabi-sabi as Koren presents it is styled, not lived. It is appreciated, but not interrogated. And like most things appreciated but not interrogated, it risks becoming decoration.

There’s an entire conversation left out about orientalism and the West’s enduring fetish for the “simple life”—where Zen minimalism is no longer a discipline but a Pinterest moodboard. Stillness becomes a lifestyle brand. Spiritual austerity is restaged in pale-toned interiors, stripped of context and contradiction. Edward Said warned us about this: how the “East” is transformed into image, not history—something to be consumed, not understood. Koren doesn’t probe this drift—he simply drifts with it.

There is also a quieter, but equally insidious, pattern: the transformation of spiritual traditions into consumable atmospheres, divorced from their roots in community and struggle. As bell hooks reminds us: the commodification of spirituality removes from it the power to transform. And Koren, for all his restraint, sidesteps this entirely. His wabi-sabi is elegant, yes—but curiously weightless. A gentle visual principle, not the ethic it once was: rooted in lineage and loss.

So yes, Wabi-Sabi is beautiful in parts. But it is also curated—eerily frictionless. I wish it bristled more. I wish it acknowledged that the aesthetic of decay becomes a luxury when it’s photographed well. That poverty, when paired with lyrical language, is called rustic. But when it is lived, it is simply called poor. Who gets to romanticise impermanence, and who is forced to survive it?

And yet—for all its omissions—the book’s imperfection made space for my own. It reminded me that not everything has to arrive answered or explained. That maybe the most important part of the work isn’t what’s presented—it’s what’s withheld.

What Koren does offer is an argument for a way of creating that resists capitalist timelines and artistic ego. It presents an ethic that stands in direct opposition to every industry metric currently shoved down our throats.

I’m thinking now: Wabi is presence. Sabi is passage. And somewhere between the two—if we are lucky—we find a way of making that feels more like devotion than display. More like ritual than release.

4.

We are addicted to arcs and conclusions. To character development as direct reward for enduring pain. We want to believe that if we suffer efficiently enough, we will be recompensed with closure. That grief will eventually become a good story. That healing will have an epilogue, and not just a loop.

But art doesn’t work like that. And neither does language. Or the body.

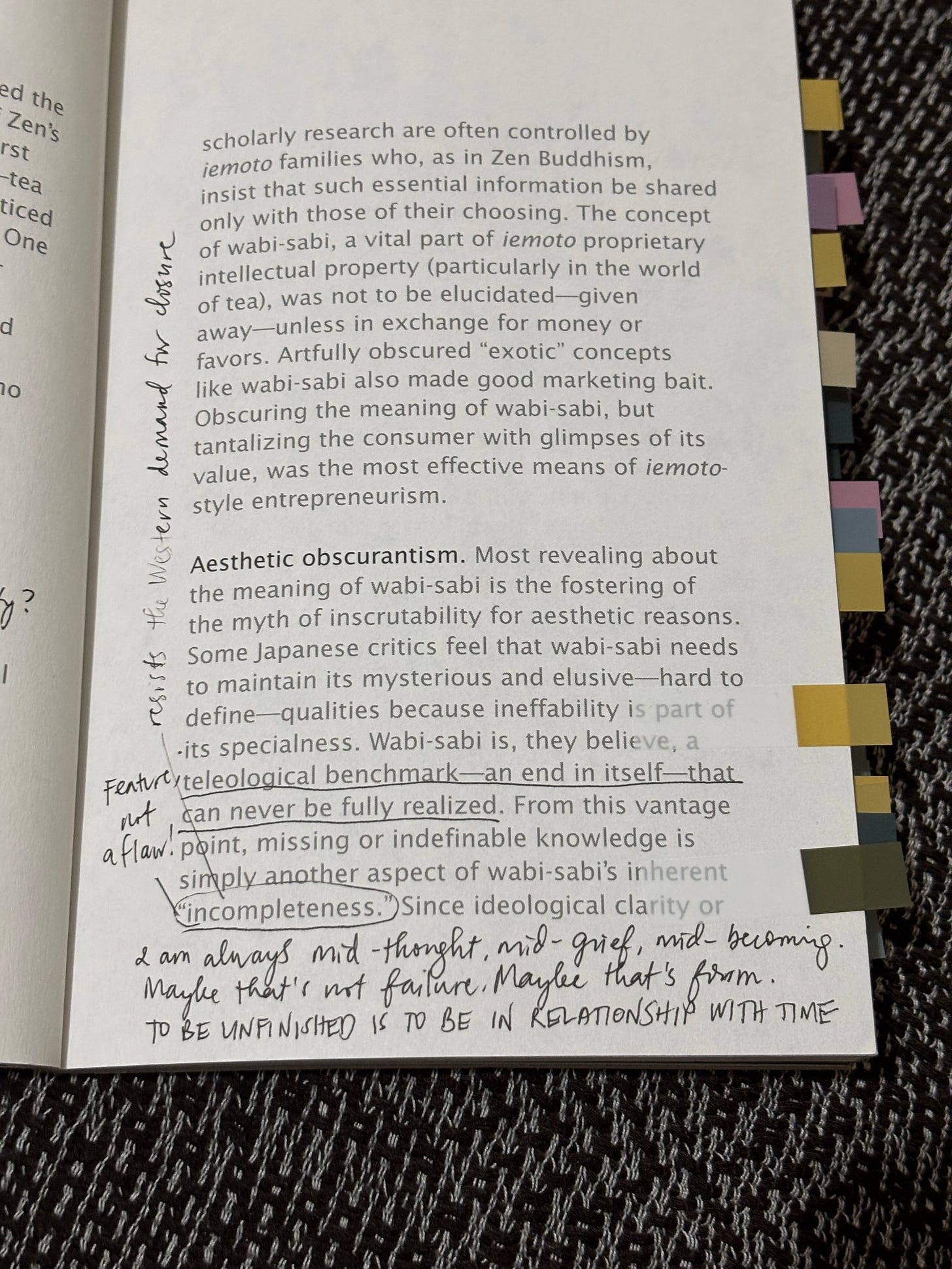

Incompleteness, Koren writes, is not a flaw in the system.

“Wabi-sabi’s inherent incompleteness…[is] a teleological benchmark that can never be fully realized.”

I believe wholeheartedly that the work of the poet is not to resolve.

I feel like to be unfinished is to be in relationship with time. The nonlinear, aching time of grief and repetition. The time of myth. The time of return.

This is a direct refusal of what the Western imagination has long held unimpeachable: control and consistency. In this framework, usefulness becomes the entry point to value—and value becomes the proxy for care. And so if a thing is unresolved, it is suspect. Ambiguity is framed as failure. To be inefficient is to be erased.

In systems shaped by whiteness, capitalism, and colonial extraction, incompleteness is punished. And so we streamline. And we tidy. And we arrive at the ending like good citizens of plot.

But what of the lives that don’t cohere? What of the narratives that refuse catharsis? What about those of us for whom resolution is not only impossible, but violent?

For artists working in the margins—BIPOC artists, queer artists, disabled artists, artists whose mother tongues have already been violated by conquest—incompleteness is not a lack of craft. It is how we breathe through the debris of cultural erasure.

We live in the rupture. In cycles. In echoes. We speak in seasons, not deadlines. In moon cycles, not five-year plans.

And what a relief it is, frankly, to stop performing improvement. To admit that the draft is always fermenting. Progress, after all, is not our native language.

5.

This is where I part ways with the notion of linear artistic “growth”—that your next work must always “level up.” That staying with the same obsessions is somehow less evolved.

Roland Barthes, in The Pleasure of the Text (Hill and Wang, 1975) once proposed the concept of the texte scriptible—the “writerly text”—as one that demands active participation from the reader. Rather than sealing itself with interpretation, the writerly text invites multiplicity and rereading.

Koren’s Wabi-Sabi, in its most generative moments, gestures toward this sensibility. A poetics not of argument, but aperture. A space to dwell, not to decode.

Too, Édouard Glissant’s notion of opacity in Poetics of Relation (University of Michigan Press, 1997) extends this further—into politics and personhood. Glissant reminds us that the demand to be fully understood is not unprejudiced. It is a form of domination. To insist that the Other become “knowable” is to domesticate. Colonialism thrives on this: the belief that what cannot be absorbed must be erased. Opacity, by contrast, insists on irreducible difference. It says: You do not get to own me just because you can name me.

If Barthes invites us to reimagine the reader as co-creator, and Glissant insists on the right to remain partially unknowable, then both point us toward a kind of permeability. A refusal to collapse into singular meaning.

This feels especially urgent for artists working against the grain of dominant systems—for whom legibility has always come at a cost. If transparency is a technology of power, then porousness might be its subversion: not a refusal to be seen, but an invitation to be encountered without being extracted. A willingness to be read, misread, and still remain whole.

And perhaps this is what my work has been circling all along—not a poetics of resolution, but of residue.

And I think: isn’t that what my poems have always been asking for? The right to disturb and unsettle?

Let my work be porous! Imagine!

Porous to what, exactly? To accident. To entropy. To untranslatable feeling. To cultural residue and familial ghosts. To mess. To noise. To meaning that shifts depending on the reader, the hour, the moon.

6.

I am always mid-thought. Mid-grief. Mid-becoming. Maybe that’s not a fiasco, maybe that’s form. My poems never land where I think they will. They’re always 80% done and 110% haunted. My life, for the most part, is a refusal of the tidy ending.

Here’s what I’m learning: Linear development is a comforting fiction and a colonial inheritance. It assumes that time is a line, not a tide. That growth is always forward. That meaning arrives in chronological order.

But that’s not how I live.

So what if we reframe the question entirely?

Not: What will this become? But: What is this becoming in the meantime?

Not: How do I finish it? But: How do I stay present to it while it’s changing me?

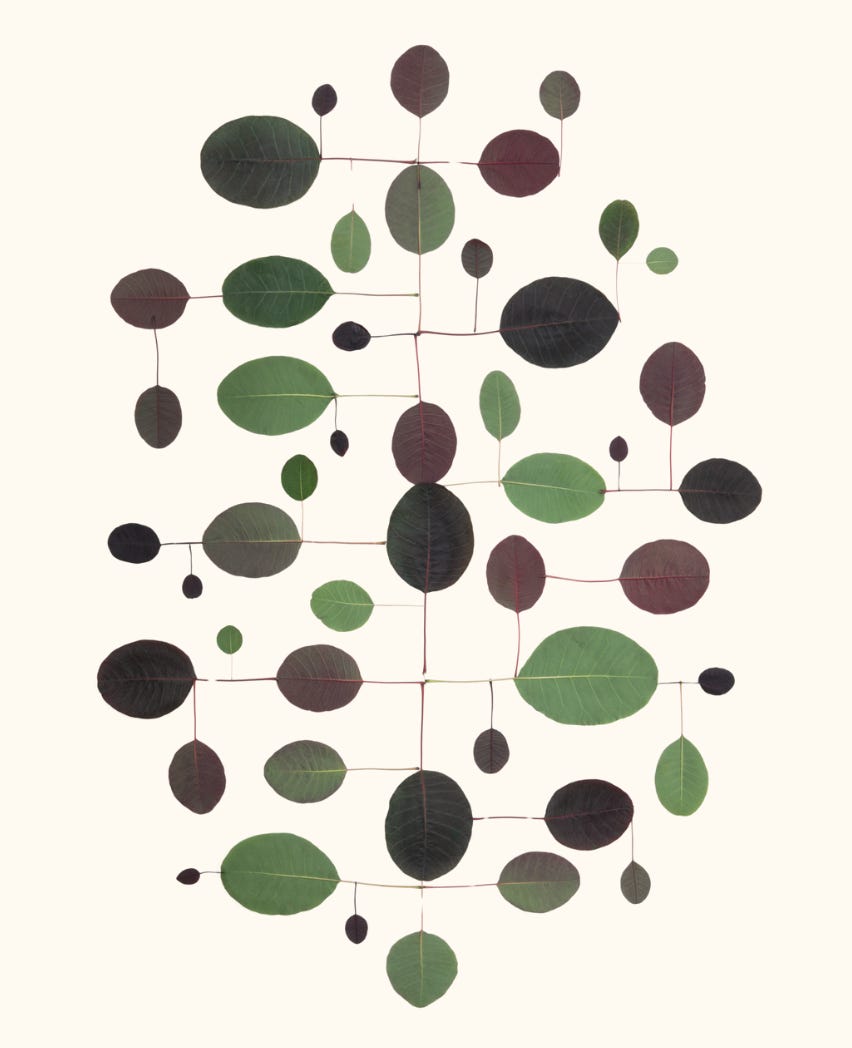

Koren writes that wabi refers to spatial events, and sabi to temporal ones. This is how I move through the world: I feel space. I archive time. What if a poem—must, can, should—hold both? A space to enter. A time to move through.

Of course, this is inconvenient for capitalism. Which makes me think—is progress a Western myth? Because art that doesn’t settle is hard to monetise. Presence doesn’t scale. You can’t sell someone their own attention span.

To resist forward motion is to resist the erasure of the present moment—something our economic systems are fundamentally invested in obliterating. And yet, that’s what wabi-sabi insists on: a rhythm that isn’t product. A life that isn’t defined by how quickly it gets somewhere.

Yes, I want to shout it to the rooftops: I want to be sustained by my art. I want a non-despairing creative life.

One where deadlines don’t masquerade as identity. One where slowness isn’t seen as threat. One where the lack of an ending is not shortfall—but the space in which something more generous might emerge. But not at the cost of being streamlined into efficiency. Not if it means outsourcing intuition. Not if it means compressing depth into content.

I don’t need to catch up. I just need to show up.

7.

Koren says the bowl is a metaphor for wabi-sabi: irregular, open at the top, free in its form. Something that doesn’t call attention to itself, but quietly insists on use.

And I think—maybe every poem is a bowl.

I’ve never really been interested in making beautiful things. What I’ve always wanted was to make honest things.

Poems that are slightly damp at the edges. Poems that smell like garlic and deadlines. Poems that hold things you’re not supposed to write about: sour leftovers, used underwear, half-finished apologies, ancestral grief wrapped in cling film.

The bowl is not sacred because of its symmetry—but because someone used it.

I think about the bowls I’ve eaten from, cried into, left unwashed beside half-written drafts. The ones I carried to bed. The ones someone handed to me after I hadn’t eaten in days. Those bowls were full of care, not composition.

Sometimes I think writing is just another way of passing someone soup. Not even good soup. Probably instant miso with too much sesame oil and exactly zero vegetables. But still. A gesture. A holding. A this-is-all-I-have-but-here-it-is-anyway.

And maybe I write poems not to preserve a self—but to pour one. To ladle something and tip it toward another hand. And trust that what spills out will be enough.

8.

Another thing that really struck me in the book is a tenet of wabi-sabi, one that says:

“To everything there is a season.”

The idea of permanence—of making something timeless—is often a privilege disguised as cultural authority. To make work that endures requires access to systems that preserve it: publishing houses, institutions, critics, archives, capital. And those systems are often gatekept by money, geography, race, language, and legacy. What we call timelessness is often just institutional preference repeated until it hardens into canon.

But what about the work that doesn’t last? Is it less real? Less worthy?

This feels crucial to say aloud in a time when creativity has been rebranded as content. When pauses are mistaken for irrelevance. When rest is reframed as laziness. When every artist is expected to become a platform, and every poem a product. It’s not just the work that is expected to be evergreen—it’s us. Our thoughts, our productivity, our presence online.

But art, real art, does not bloom all year. Wabi-sabi says: what dies returns as something else.

Seasonality is not a collapse. It’s rhythm. It’s compost. It’s the quiet alchemy of decay and regeneration. It is saying over and over: Trust the fallow.

Oh, how hard that is for me—to watch the field lie empty and not panic.

I panic that I’ve lost it, that I’ll never write again, that everything I’ve made was a fluke. The silence after a finished project often feels less like peace and more like abandonment. The calendar is empty and I feel like I’ve died a small, unremarkable death.

Trust the fallow. This demands a different theology. A different relationship with time and output. It suggests that absence isn’t lack—it’s labour beneath the surface. It asks me to believe that rest is not the opposite of work, but a continuation of it in another form.

This was not how I was raised. I was taught that value lies in use. That a break means you’re falling behind.

But what I want—and am only now beginning to say with any confidence—is a life of seasonal devotion. A rhythm of ebb and return. A reverence for the fleeting. A willingness to bless what ends.

9.

Maybe you’re in a season of pause. Maybe the field is quiet. Maybe you’re still composting something old, and you don’t know what (or who) you’re becoming yet.

If that’s where you are—this is for you.

Here’s a prompt: Begin with a bowl.

Make list of bowls you carry. What do they hold? What spills when you’re not looking? What have you tried to scrub clean, but can’t? What refuses to stay empty?

Be as literal or surreal as you like. A bowl of your mother’s laugh. A bowl of 3AM ramen and regrets. A bowl passed from cupboard to cupboard. A bowl that holds buttons or beets.

Let the bowls be cracked. Let them wobble. Let them leak onto the page. Don’t worry about form—just pour.

(And if you end up writing an actual inventory of your kitchenware? That counts. We honour all sacred vessels here, including the ones from Daiso.)

10.

Finally a poem:

A Brass Bowl

Wendell Berry

Worn to brightness, this

bowl opens outward

to the world, like

the marriage of a pair

we sometimes know.

Filled full, it holds

not greedily. Empty,

it fills with light

that is Heaven’s and

its own. It holds

forever for a while.

Celebrating & Amplifying

Sharing some recent news from friends and people I admire that you should check out—poets, artists, thinkers, and makers whose work deserves more eyes, more ears, more hearts. If you’re looking for something new to read, listen to, or witness, start here:

Nick Martino and Tom Snarsky have new work out in Issue Eight of Frozen Sea.

Nick also has a new poem in Issue 76 of Hayden’s Ferry Review: “Where do I begin—with what beginning?”

Congratulations to Emmanuel Oppong-Yeboah, Boston’s new Poet Laureate!

“I turn most into / Myself. I clap my hands // Once more, twice, / Huddled against shadow, / In wait of an encore” — Kami Enzie has a new poem at American Literary Review. (Also another one in Fruit.)

I loved this recent episode of Poetry Off the Shelf with Tiana Clark.

Noel Quiñones has a book coming out—Orange, to be published by CavanKerry Press, in 2026. Also, how lovely is his poem, “Orange,” in Poem-A-Day: “Scraped from dust to crown our bruises, warriors we / stared directly into the sun, Tainos dyed in orange / As if we always knew we were history.” Felicidades, Noel!

Patrycja Humienik and David Naimon talk about forms, the water, the body, and her book, We Contain Landscapes, in this episode of Between the Covers. She is also going to teach On Rivers: A Generative Poetry Workshop over at Brooklyn Poets.

Mandy Shunnarah has two poems in The Dodge Magazine: “I take what calls to me—what wills itself to be found. / I don’t seek this fortune; these riches search me out.”

Katia Engell is a brilliant artist and poet and her latest Substack post in Relate/Create talks about relational caring, our relationship to memory, and how care and creativity lives in the body.

Dead End Zine’s new co-editor is the lovely Ashna Ali, and the fourth issue features some of the most amazing poets I know: Rachelle Boyson, abeo tisdale, and Kristin Lueke.

Also, Yomalis Rosario interviewed Ashna in Literary Liberation: “Writing requires an emotional nudity that prompts a similar ethic in liberation work.”

I cannot wait to get my hands on Alina Stefanescu’s new book, My Heresies, published by Sarabande Books.

“How could we have lost what made / such sense of us?” — this new poem by Maya C. Popa in The New Yorker is everything.

Jenny Molberg is the new editor-in-chief of Ploughshares! What amazing news.

The New Economy, Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s new book, published by Copper Canyon Press, is going to be out soon in the world. October cannot come soon enough.

Nur Turkmani is one of the Anthony Veasna So Scholars in Fiction. Her work, “Dead Fish” is out now in The Adroit Journal.

“Maybe it conjures up frolicking foxes / for him, a fat pear moon drawn / by Miyazaki.” Dominique Ahkong has two poems in Volume 62 of The McNeese Review.

Join Talicha J at an open mic to celebrate her book, Taking Back the Body.

“My neurologist said I made a fast and strong (and unexpected) recovery because I was a poet and a painter, because I knew a few languages. I had multiple engines, multiple strategies for making meaning.” Five new poems and a conversation with Richard Siken in The Common.

Still sitting with this new work, “Slow Violence,” by Sarah Ghazal Ali at Poetry: “There is a symbolic difference/ between distance and direction.”

Bloodmercy by I.S. Jones is available for pre-order! I’m so excited for this. It was chosen by Nicole Sealey as the winner of the 2025 American Poetry Review Honickman First Book Prize. The cover is so gorgeous. I’ve loved Itiola’s work since I first read her chapbook, Spells of My Name (Newfound, 2021).

Itiola is also teaching a workshop over at Brooklyn Poets—Duality of Holiness: Of Mental Illness and the Oracular.

More Brooklyn Poets workshops: Writing Parents, Family & Family Ghosts by Gbenga Adesina, A Little Class on Form by Jaz Sufi, and Getting Your Poems Out There: A Submission Intensive by Tara Skurtu.

José Olivarez is back on Substack with Office Hours. Yes please!

“I thought about all the things my mother taught me to hold onto as a young girl growing up Asian in America: time, money, self, and dignity. What does loss look like?” Really enjoyed reading this work by Joyce Chen, who will be reading at Other People’s Poems later this month.

Hiwot Adilow has new work upcoming in the pilot issue of Abolition Journal.

“I’m always writing to you / to remind myself that all love poems are about the future.” So much yes to this new poem, “Bird” by Tomás Q. Morín, at Poem-A-Day.

Susan L. Leary has new work at Poetry Online: “The ear / patrols. The heart patrols. The hand steadies the head & the stomach / explodes inside the gut.”

Yours,

T.

A fellow Substacker directed me to your work, and I’m so grateful they did! This post expresses so many things that I’ve been holding and sifting and trying to live into - but in words far more beautiful than mine. Thank you!

Also this paragraph put such a smile on my face because the language so closely mirrors a short poem I wrote recently (inspired by the way my chronically ill body resists all of my best laid plans and attempts at artistic deadlines) - “And maybe I write poems not to preserve a self—but to pour one. To ladle something and tip it toward another hand. And trust that what spills out will be enough.”

Here’s the poem:

Never mind then -

I’ll just pour myself

in the bowl of the earth,

let my heart be ladled about.

There are worse fates

than being

delicious.

I'm right there with you! it’s one thing to swear off panic as a career strategy; it’s another to wake up and realise you have no map once you let go of fear." You've expressed it in such a profound and insightful way. Thank you!!